JULIA A. IRWIN: You hold the Photographic Knitting Club sessions virtually, and participants learn photogrammetry while moving about and photographing their own homes. Photogrammetry has historically been deployed in the service of state-sponsored surveillance. Can you talk about the concept for Photographic Knitting Club in relation to this juxtaposition of surveillance technique and domestic space?

ROSALIE YU: My art practice explores how we might engage with phototechnics and digital technology in ways that rewrite power relations by centering care and shared intimacy, something I draw from many feminist forebears. As you note, in Photographic Knitting Club the focus is photogrammetry. Like many technologies, the earliest uses of photogrammetry were in the context of imperialism and war. In World War II, the military obtained 3D measurements from aerial photographs using this technique in order to produce precise targeting maps

1

ASPRS Film Committee, “Geospatial Intelligence in WWII” (ASPRS The Imaging & Geospatial Information Society, May 2009), digital video, 2:00, https://www.asprs.org/news/asprs-films/asprs-films-viewer.html.

. Today, you see photogrammetry in similar and many additional contexts. Gaming developers use it to build 3D worlds with a photorealistic effect. Western institutions like the Smithsonian are 3D scanning often-appropriated cultural belongings as a means of (digital) preservation for an imagined Western audience.2

“Welcome to the 3D Scanning Frontier,” Smithsonian 3D, https://3d.si.edu.

There are inexpensive phone apps, so that most people can 3D scan physical objects and create digital novelty items. This relative accessibility is a draw for me, because it lends a pedagogical and participatory point of entry. I am interested in how these tools can be taught, unlearned, and reframed. In the workshops, as participants learn photogrammetry, we are also studying and problematizing the apparatus.Apart from its application to surveillance, I like to see photogrammetry as a craft that sits between photography and sculpture. The software makes a 3D model by stitching several images into topographical digital surfaces. Connecting the mechanics of scanning with the gesture of stitch and repair, I started thinking about knitting clubs, or “stitch ’n bitch” circles. As people come together to knit, the community aspect becomes more important than the result of their threading. Borrowing from that framing, I created Photographic Knitting Club, a virtual space to gather and check in with each other. Instead of knitting yarn into scarves, we knit our home spaces together from images.

Another prompt for this project was the fact that I had to leave the U.S. in 2019 due to immigration issues. I felt Zoom fatigue before it was a thing. Then the pandemic hits—suddenly everyone is on video chat. Everyday life is entirely domestic. Webcams are the window, both in and out. I started the workshops as a way to reassert some agency over how technology interfaces with our lives.

JAI: After the workshops, participants send you their photographic datasets, which you then use to make 3D models of their homes. Those models form the working medium for the abstract artifacts. We might call this handoff from workshop collaborator to artist a non-extractive data exchange, a handling of personal information that resists its commodification and instead emphasizes care. How do you approach working with this intimate material?

RY: The helpful guiding principle is to not put people’s space on display and to avoid any urge to present a photorealistic, real estate-style rendering. The exchange is an exercise in my own empathy, in two parts. First, as I engage with someone’s data I develop a sense of connection to them. However, peeking into and literally playing with people’s homes in 3D software makes me uneasy, especially because I am quite private myself. Second, then, I try to anonymize their space through aesthetic abstraction, using my personal digital privacy concerns as a guide.

JAI: In data science, anonymizing can mean taking potentially identifying information and “zooming out,” so to speak, to make it fit a broader category—instead of 36 months of age, one is 0–5. You anonymize by working in the opposite direction, focusing on the singular details of, say, the pillow someone slept on last night. Yet, you preserve their anonymity by way of a carefully considered frame.

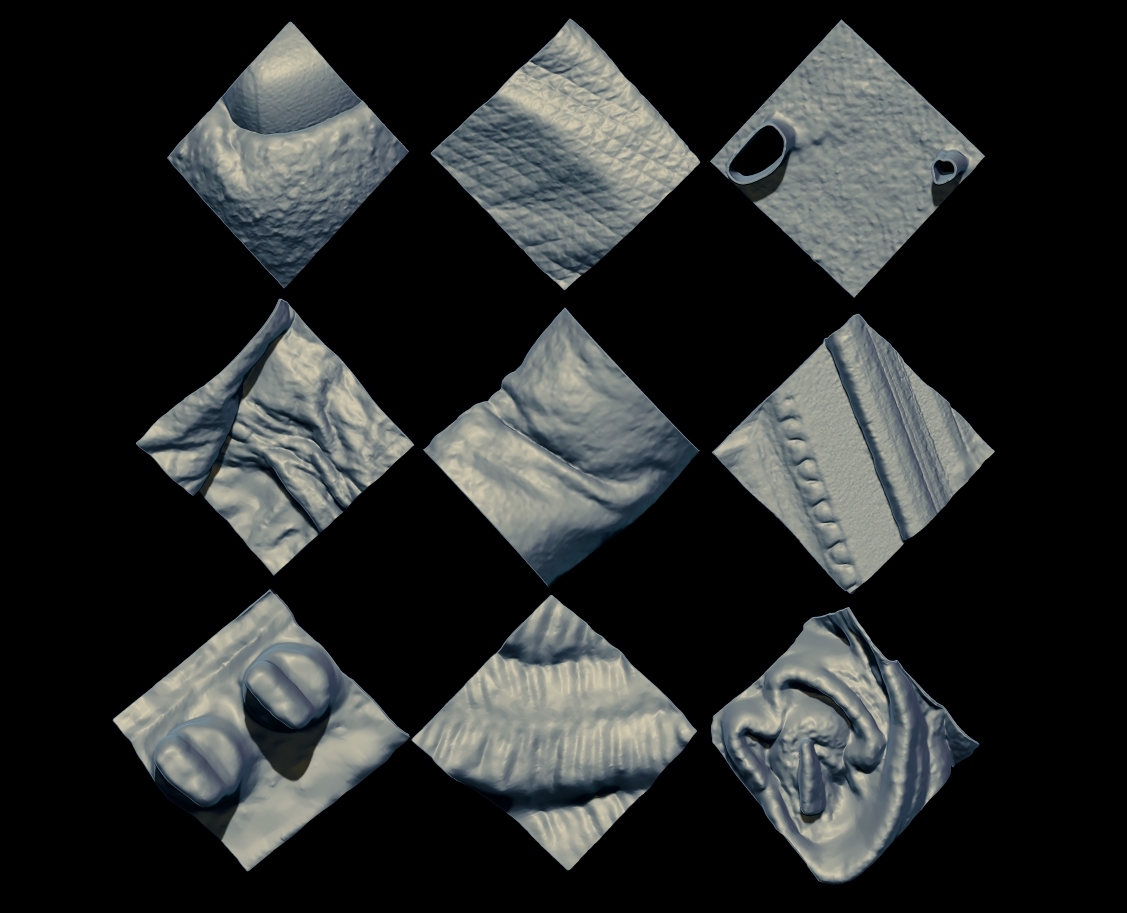

RY: I see myself as an archaeologist, digging out the proof of living from the resulting 3D models but not performing identification. I look for details that might otherwise get lost in accretions of data. In one model, I discovered that the blanket strewn on the sofa had a pattern of baby carriages. I then imagined this participant as a new mother, caring for a baby on that couch. Artist Alan Warburton says my process is like revealing the greenscreen in a broadcast studio, or like discovering the TV host isn’t wearing pants. Instead of highlighting particularities as identifiers, I aggregate, reorganize, and introduce new figurations. The resulting artifacts bear the imprint of my own positionality, fictionalizations, and idiosyncratic process of selection.

JAI: We think of data as immaterial, as a phenomenon that is non phenomenological, because it cannot be sensorially experienced without being constructed into a different form. Your process starts with digitized, photographic datasets, but many of the artifacts you create by hand, by drawing or weaving paper. Can you share how bodily engagement factors into the workshops and finished pieces?

RY: I think a lot about how this measurement tool, which is rooted in science and math, can come into alignment with our experience and intuition. The software’s algorithm needs certain things from the image datasets (and from us, the photographer) in order to produce a model. During the data collection process, when we take a series of photos, our practical knowledge of our domestic space (such as the shortest path from the bedroom to the bathroom) is confronted with our guessing how the computer wants us to photograph. Today our experiences are so thoroughly mediated by screens and digital technology, and a casualty is perhaps our bodily memory in relation to our surroundings. Paradoxically, the computer vision algorithm’s choreographing of our bodies, its invitation to wander through a familiar space in an odd way, heightens our awareness of our objects and habits.

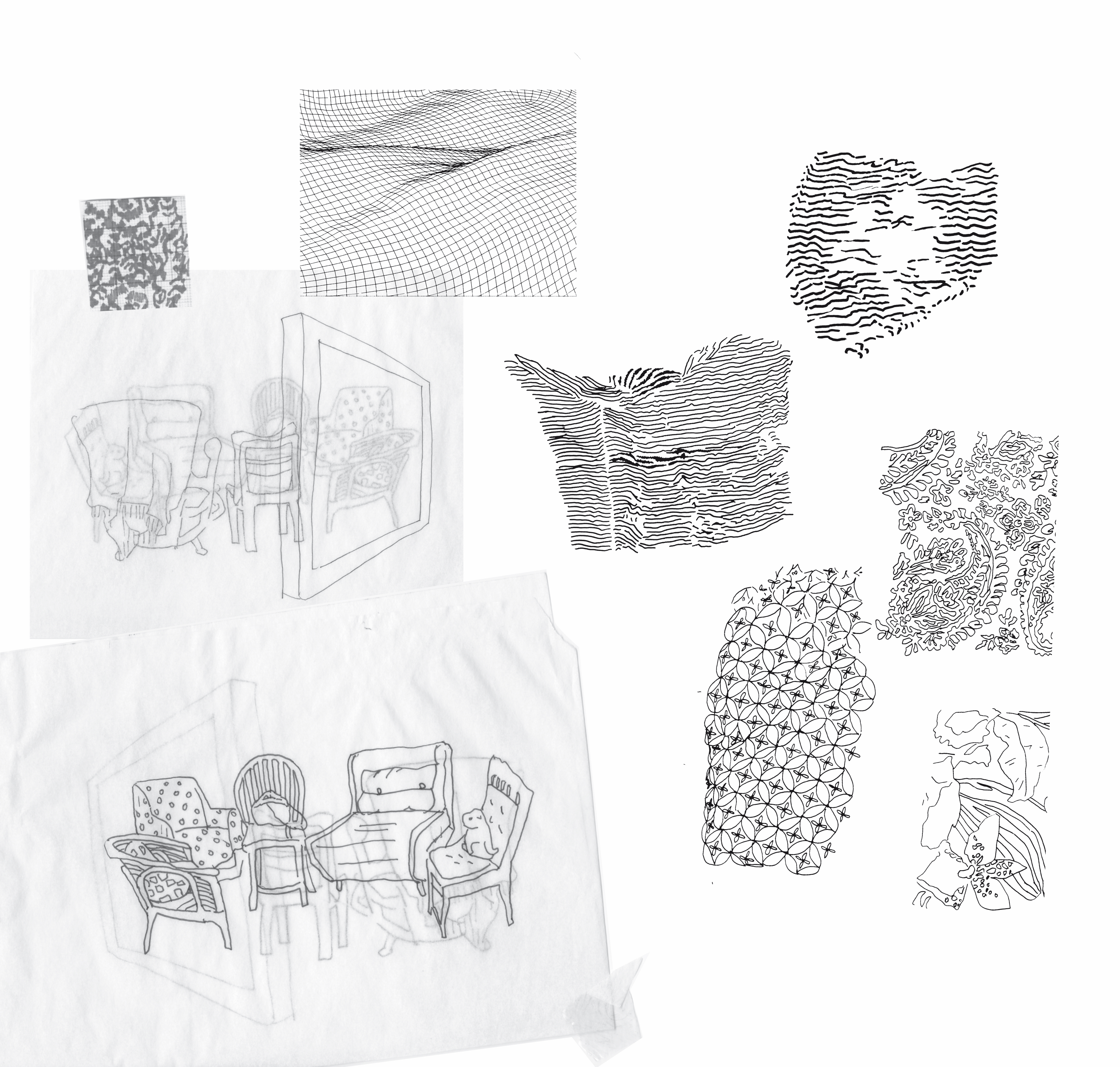

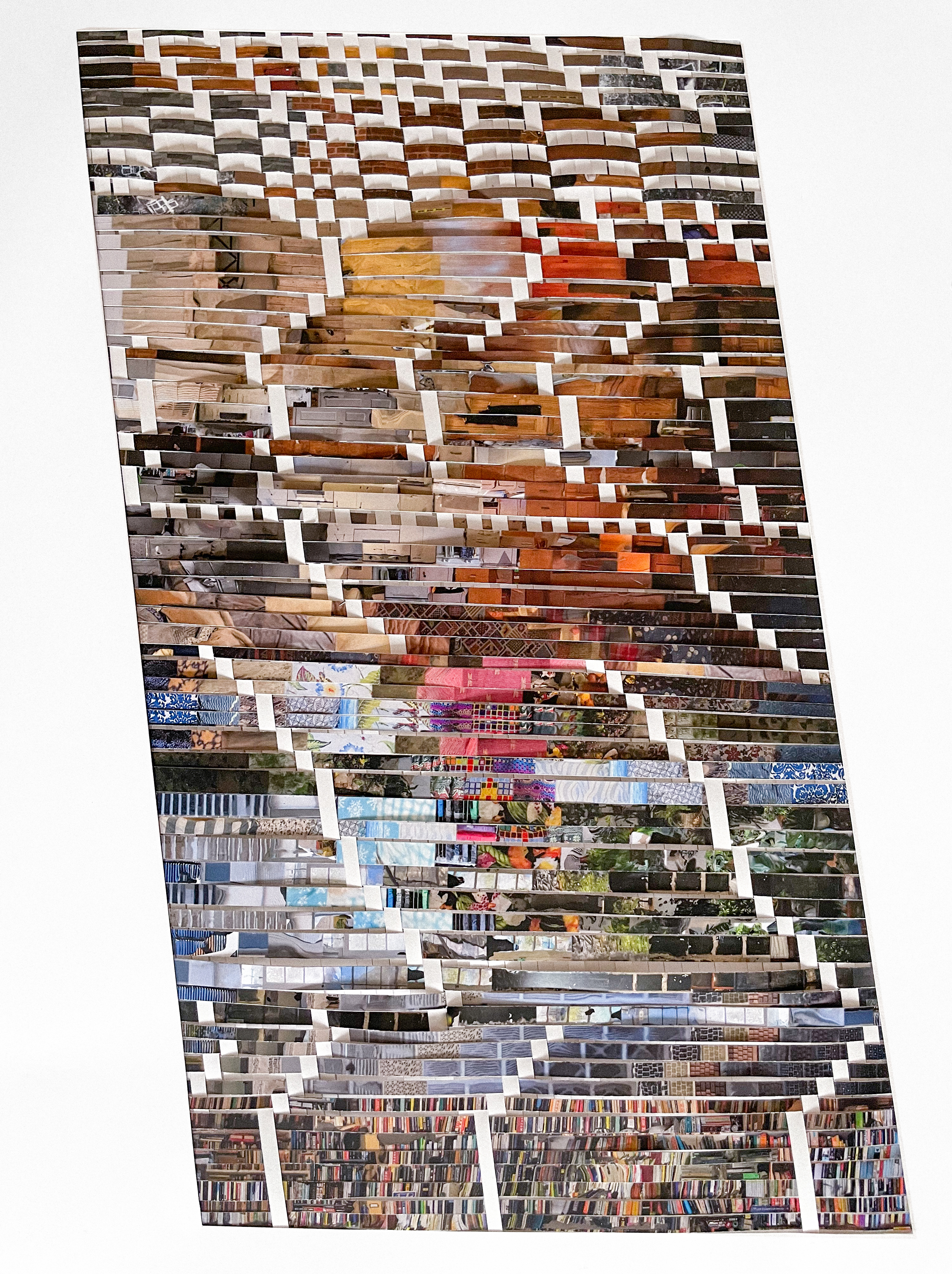

My interest in reframing digitizing technology as a digital craft extends to both process and output. For the Refamiliarization exhibition, I performed handicraft on the photogrammetric data to draw out the software’s materiality and to subvert qualities associated with surveillance, such as remoteness, immediacy, and a totalizing view. Photogrammetry software allows one to observe models of participants’ homes in ways that are humanly impossible, from angles and at scales we could never inhabit in space and in juxtapositions we could never experience in time. I started by playing with these composited points of view and printing out tightly cropped 2D renderings of the 3D models, then tracing by hand the detailed features. Tracing acquainted me with the common objects found in every space—floor boards, books, air conditioners, keyboards—and the logical similarity of different fabric patterns, such as the baby carriages, when alongside one another. I then developed my own classification system, cut up complementary components from different environments, and wove them together into a tapestry. Manual and slow, the process transformed digital information into a new (old) mode of visualization.

JAI: One of the pieces, Suspended Reliefs, No. 6, is a wall-mounted grid of cubes, each with a glitchy photographic texture projected onto it, and a number of transparent resin tiles are arranged throughout. What is represented within this piece and what is the significance of its formal presentation?

RY: Sometimes the photographic datasets I received contained aberrant features and the software’s resulting 3D models were distorted. They appeared as fractured, melted, or suspended pieces of environments. For example, cats flying in the air or a mirror that’s a portal to a parallel space. These fragments were the results of the software’s guesswork at filling in gaps in the data. I found that this archive of distorted models resembled the aesthetics of Pompeii. These “domestic ruins” are of the spaces that once contained, protected, and even alienated the workshop participants during lockdown. I started researching how, in the wake of disasters, people return to sites of destruction to mourn and rebuild. I became a student of the monument form.

This piece, made of 3D prints and 18 paper cubes each textured with a distorted model, is a monument to the sites where we witnessed, even if just through screens, the destruction wreaked by recent events. The purpose is to create a space that doesn’t privilege the synthesis of knowledge but rather functions like a meditation zone, articulating the coexistence, yet discordance of the digital and physical, the ephemeral and whatever we choose to preserve.