the representation of otherness

Ça Parle Defined

Lisa Neal

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

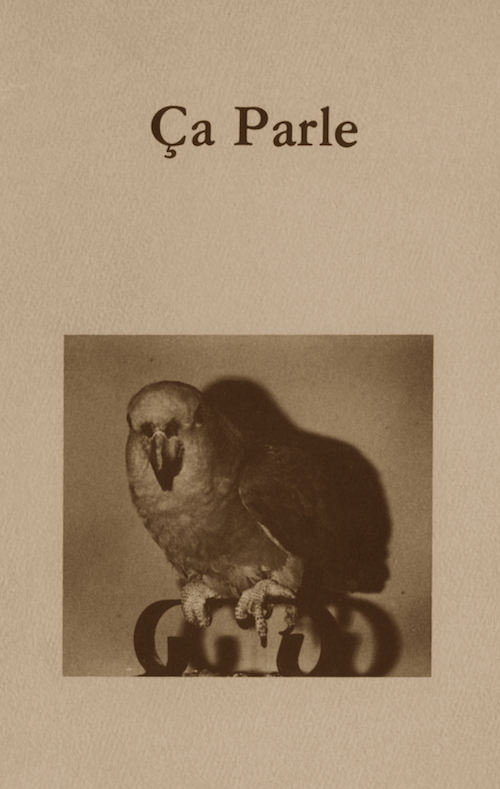

Ça Parle [sa parl], n. 1. a polyvocal organ spontaneously generated to counteract both a mutism and a dispersion of voices. 2. a voice from the western extremity of the country to assert the presence of new sounds in the cacophony of French letters. 3. a locale of speaking and of writing whose borders are defined only by the limits of funds.

A certain insidious mutism launched our effort to found Ça Parle, a graduate student literary journal. To end silence one speaks--but from what privileged location, with what currency of exchange (what language, what medium, what money?) and above and in all, about what?

Read now at JSTOR

Mimus Polyglottus

Avital Ronell

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

(Note: The following wisps, or stenographs, are drawn and regathered from a work concerning a discourse of effacement. The title refers to a partially excluded narrative on mimesis and structures of naturality. It won a contest against another, perhaps more telling contendent for title role, which was "The Bird as Metapsychological Fact." Be that as it may, when situated within a strictly academic taxonomy, the Mimus Polyglottus can be translated into a relatively fragile branch of comparative literature--hence its edge over the metapsychological fact. What follows (and necessarily what does not follow since there will be a breach of logic, a solicitation of madness) is intended to take the place of congratulatory vegetation, such as a bouquet of flowers sent to the offices of Ça Parle, whose precise locality I do not know. All I remember is the projected cover, described to me a few months ago by Lisa Neal: a kind of speech-related bird...

Read now at JSTOR

Philippê*

Pamela Roberts

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

La petite place somnole encore à cette heure-ci. Ne voulant pas manquer le seul car qui parte le matin pour Pythagoréon, je me suis levée tôt pour marcher en bas de la côte. En attendant, assise à la terrasse d’un café du port, je prends un café turkiko.

Ce lendemain de fête, enfin, la mer est calme.

Que le temps était différent il y a trois jours quand j'ai pris le bateau au Pirée. J'y étais arrivée tôt ce matin-là aussi. Et heureusement encore. Il y avait déjà du monde sur le quai.

Read now at JSTOR

Montaigne: Mask and Melancholy

Patricia Teefy

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Death occupies a central position in Book One of Montaigne's Essais. Not only does Montaigne insist on the necessity to constantly reflect on death, he places death in exactly the center of his first book under the title of friendship. Montaigne's essay "de l'Amitié" becomes a manifestation of the preoccupation with death that he exposes in "Que Philosopher, c'est apprendre à Mourir." Mourning the loss of his friend Etienne de la Boétie, Montaigne centers his essay on friendship around the very object that initiated its production. In an attempt to represent the lost "La Boétie" and the plenitude he offered, Montaigne's discourse can be seen as a symptomatic result of the pathological and psychological "humour" melancholy. A look at the notion of melancholy in the work of the sixteenth-century anatomist Robert Burton, and at Freud's essay, "Mourning and Melancholia," will support my theory that Montaigne's text, in particular the essay on friendship, is in fact a melancholic text.

Read now at JSTOR

Le Couteau de l’Autre, Un Regard sur Leiris*

Lisa Neal

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Bien que Leiris ait dédié son autobiographie L’âge d'homme à Georges Bataille comme “l’origine de ce livre,” il a placé en tête du livre deux figures peintes par Lucas Cranach. Le diptyque présente à gauche Lucrèce, femme violée avec poignard posé, la poitrine déjà tâchée du sang qui coulera bientôt de sa plaie fatale, et à droite Judith, héroïne juive, immortalisée sur la toile après avoir sauvé son peuple par la décapitation du roi ennemi, Holopherne. Ces deux femmes, presque identiques ayant toutes deux le sexe légèrement voilé, occupent l'espace primaire du livre. Leiris parle de la dette qu'il leur doit, “de là m’est venue l'idée d'écrire ces pages, d'abord simple confession basée sur le tableau de Cranach et dont le but était de liquider, en les formulant, un certain nombre de choses dont le poids m’oppressait, ensuite raccourci de mémoires, vue panoramique de tout un aspect de ma vie.” L’aspect dont parle l'auteur c'est l'aspect érotique de sa vie passée et de ses fantasmes.

Read now at JSTOR

Madame Bovary in the Consumer Society

Thomas F. Petruso

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

George Perec's Les Choses marks a turning point in the development of the post-war novel insofar as it reworks the tired theme of alienation into the specific context of the Sixties' social dynamic. That is, what we see here is no longer Man confronting the abyss of his existence, but rather lost in the myths of advertising. The novel is informed by the critical tradition which underscores the inauthentic nature of Man's rapport with World in a technical age, and it uncannily anticipates the analysis of Baudrillard's Société de consommation. Les Choses is indeed the novel of the Consumer Society: a tale of self-image derived from media-conditioned perception of reality. The theme of self-image distorted through media in the broadest sense can, of course, be traced to Cervantes, but Perec's more immediate model would seem to be Flaubert, in whose novels he has found the seeds of social phenomena which will come into full flower a century later in the post-war boom economy.

Read now at JSTOR

Manque de Sujet––Sujet du Manque: Réflexions sur la fonction de l’absence dans les Lettres de la religieuse portugaise*

Andreas Illner

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Pour qu'il y ait fiction d'amour, il faut qu'il y ait désir et manque. Peut-on s'imaginer un roman d'amour qui parlerait seulement du comblement et du bonheur parfait? Le bonheur y est toujours une fin (finalité et point final), tout au plus un début ou une étape vite interrompue par quelque obstacle intérieur ou extérieur. La vie a beau continuer, comme indique la formule à la fin des contes de fées, mais le discours s'arrête. Car le bonheur est simplement indicible (n'est pas de l'ordre du langage) ou serait trop vite dit, répétitif, ennuyeux. Il faut l'obstacle qui sépare les amoureux pour créer le texte: le mari détesté ou la femme jalouse qui s'opposent à l'adultère, deux familles qui se haïssent et qui font tout pour empêcher les enfants de s'aimer, un rang social trop différent qui interdit la réalisation de l'amour, bref, l'ordre social qui interfère; ou une séparation imposée par les affaires, une guerre, un travail à accomplir; les variations de l'obstacle sont interminables, engendrent des aventures sans fin.

Read now at JSTOR

Poétique et Politique: le paradoxe de la représentation de l’autre dans le Supplément au Voyage de Bougainville*

Mira Usha Kamdar

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Sie können sich nicht vertreten, sie müssen vertreten werden.

–Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

Comment faire parler l’autre? La poétique de Diderot conspire par son dynamisme et sa polyvocalité à suppléer au mutisme de l'autre, femme ou Tahitien. Ainsi on a longtemps vu en Diderot un des premiers champions dans la lutte contre l'oppression des institutions telles que la vie monastique, le mariage et la colonisation. Or chez Diderot la condamnation de ces institutions confère une autre sorte de privilège au sujet occidental et masculin. Malgré un effort héroïque pour effacer sa propre voix pour que l'autre puisse s'exprimer, c'est quand même toujours la parole de Diderot qui sort de la bouche Tahitienne ou féminine. C'est le paradoxe de la mimésis diderotiste, car l'auteur qui ne se trouve nulle part dans son récit est aussi partout.

Read now at JSTOR

*Published in French

Volume 1.1 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.