Articles

Regarding the Cave

Adriana Cavarero

Translated by Paul Kottman

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

There is a fresco by Vasari which alludes obliquely to Plato's cave. A

man is seated in the space between the flame of a brazier, which

burns behind him, and a wall in front, on which his shadow is projected. The fresco is called The Invention of Drawing: the man is an

artist. He follows in pencil the profile of the shadow, tracing the

design on the wall. The mechanism of the projection allows him to

function, at once, as subject and object of the same representation.

He produces and reproduces the same image. On the wall is fixed

the profile of a shadow which is destined soon to disappear: when,

for instance, he rises, turns and leaves the room.

The situation in Plato's cave is obviously much more complex.

The men who are seated are numerous, and they are all prisoners.

Bound so that they cannot even move their heads, they are confined

to one sole activity: seeing. Behind them is a wall, behind which

other men pass by in a line, carrying statues and simulacri on their

shoulders. Further behind, there is a fire whose light casts the shadows of the simulacrum onto the back of the cave. Caught in a

representative mechanism of which they know nothing, the prisoners see mobile shadows on the wall of the cave in front of them.

What is certain is that they are forced spectators, not artists. The

artist is Plato.

Read now at JSTOR

Misreading as Canon Formation: Remembering Harold Bloom's Theory of Revision

David H. Wittenberg

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In recent years, Harold Bloom has become one of the best known

literary critics writing in English, on the selling strength of a string of

books on Western literature and religion. At the same time, his most

crucial theoretical insights about revisionism, poetic influence and

the formation of literary canons have largely been set aside or forgotten by those writers within the academy most likely to appreciate

them. The thoroughness of this dismissal may be gauged by the fact

that John Guillory's Cultural Capital, perhaps the most important and

theoretically astute recent work on the formation of the English literary canon, declines even to mention Bloom, who is still among that

canon's most historically crucial theorists.

But Bloom's backslide within academic theory is in large part

his own doing. Even more than most writers, he has been of little

help in determining what of his own theory remains worth reading.

In recent years, despite his stated preferences, he has become a pundit

for a traditionalist and preservative view of the inherent, ahistorical

"qualities" of certain Western texts, asserting that canonical literature is something you "recognize when you read it," and, more

generally, that works are canonized because they, or their authors,

appear to possess certain attributes.

Read now at JSTOR

To introduce Pierre Fédida

M. Stone-Richards and Ming Tiampo

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

To say that Pierre Fédida is a member of the Association psychanalytique de France (APF), which includes Jean-Bertrand Pontalis, Jean

Laplanche, and Didier Anzieu, and that his work is closely related to

that of André Green (Société psychanalytique de Paris), is scarcely

to begin to situate him. Fédida‘s distinctiveness in part resides in the

fact that he is the heir to a tradition of philosophical and psychopathological thought that is strictly phenomenological and

psychoanalytic, yet which has long recognized the critique of the

institutionalization of psychoanalysis. His work also demonstrates

an extraordinary openness to and fertile dialogue with English language clinical psychoanalysis (for example, the work of Harold

Searles, D.W. Winnicot and Frances Tustin). In other words, his is a

psychoanalysis perpetually interrogating experience in which the

usual oppositions between the psychoanalytic and the phenomenological do not make sense. His project is as much concerned with

the mutual critique of phenomenology and psychoanalysis as it is

with the furtherance of critical experience. It would be useful, though,

to identify briefly certain key themes which dominate a large oeuvre.

Read now at JSTOR

The Movement of the Informe

Pierre Fédida

Translated by M. Stone-Richards and Ming Tiampo

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

“A dictionary would begin from the moment where it no

longer gave the meaning but the job of words. Thus

informe is not only an adjective having such and such a

meaning, but a term which works to disorder, generally

requiring that each thing take its form. What it designates

doesn't have rights in any way, and is crushed everywhere

like a spider or a worm. It must be that the universe takes

form in order to make academic men happy. All of philosophy has no other goal: it consists of giving a redingote

to that which is a mathematical redingote. Affirming

oppositionally that the universe does not resemble anything and is but informe comes down to saying that the

universe is something like a spider or spittle.”

––Georges Batailles, Documents

Georges Bataille's denunciation on several occasions of the threat of

psychoanalysis' circumscription by the auto-dogmatization of its

vocabulary would not be worth recalling again today if it did not

take on a kind of decisive significance here. A dictionary is in the

service of the use and functional usages of the defined words, and it

confirms the knowledge of a language in its principal, instrumental value of communication. Whatever the rupture that it introduces -

through the place it allots to sexuality –– to the principle of an intersubjective communication, psychoanalysis perhaps does not escape

the destiny of the spirit of the dictionary: the stake is no less than that

of repression undergone by the words of a language from the moment that their objective meaning is privileged over their "business" –– most certainly their work, but also their auto-eroticism and in this

way the pleasure [jouissance] of playing with them.

Read now at JSTOR

The Law of the Outlaw: Family Succession and Family Secession in Hegel and Genesis 31

Gian Balsamo

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

An analysis of the structure of the Hebrew family in the Old Testament may help set in play a deconstruction of Hegel's views with

regard to the contributions given, respectively, by the Roman and

the Christian family to the formulation of a private code of law and

particularly of the law of legitimate family succession. According to

Hegel, family succession earns its legitimacy through the determinant role played by the paterfamilias, the head of the family, in the

transmission of the family's name and estate. As Jacques Derrida has

shown in Glas, the principle that a historical and logical progression

necessarily leads from the Greek to the Roman and from the Roman

to the Christian notion of paterfamilias is fundamental to the Hegelian

jurisprudence of civil right. Yet, the necessity of this progression is

contradicted by the structure achieved by the Hebrew family through

the Mosaic law. A gulf separates the Christian family, whose essential manifestations are characterized by the love of one's kin, and

ultimately by the love of the Holy Trinity, from the Hebrew family,

whose essential manifestations are characterized by tribal norms,

and ultimately by the dictates of the Torah.

Read now at JSTOR

Blanchot ... Writing ... Ellipsis

Michael Naas

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Were it possible simply to add an ellipsis onto all that has recently

been written about the work of Maurice Blanchot, I would be very

tempted to do so. I would be tempted to translate everything that I

would have written, along with everything that I could never write,

into a simple ellipsis, which I would then offer up as my best line of

thought, as a perfect circle of writing, as an ellipsis that would thus

already be beyond me, excluding me from it from the very beginning.

Such is, I think Blanchot has suggested, the temptation of writing, the temptation to go beyond writing in writing, to say it all without

infidelity or remainder, to write so simply, so simply, so simply ––but without and beyond repetition. To write with a single ellipsis

without remark, with a simple ellipsis that would overcome its own

spacing, its own temporalization: with an ellipsis, so to speak, of the

unspeakable.

Read now at JSTOR

Book Reviews

On Frederic Spotts’ Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival

Daniel H. Foster

A review of Spotts, Frederic. Bayreuth: A History of the

Wagner Festival. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996).

Read now at JSTOR

On Lisa Jardine's Reading Shakespeare Historically

Paul Kottman

A review of Jardine, Lisa. Reading Shakespeare Historically. (New York: Routledge, 1996).

Read now at JSTOR

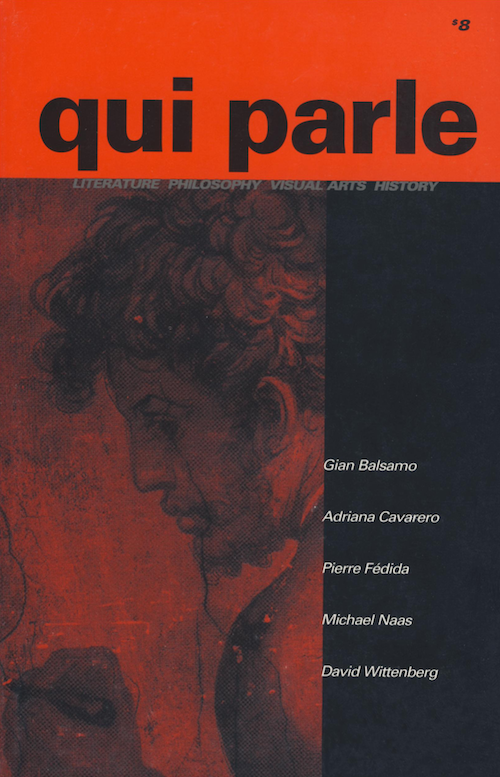

Cover: Detail, Giorgio Vasari, La scoperta della pittura e particolari. Courtesy Casa Vasari, Salla delle Arti e deglie Artisti, Firenze

Volume 10.1 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.