Articles

Psychoanalysis and the Enigmas of Sovereignty

Eric L. Santner

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In a brilliant and, I think, insufficiently appreciated, essay on Freud,

Harold Bloom situates Freud's conception of love somewhere in the

interstices of Greek, Judaic, and Roman culture. On the one hand,

Bloom suggests that Freudian Eros is more Judaic than Greek, "since

Freud interprets every investment of libido as a transaction in the

transference of authority" (RST, 147) whose ultimate point of reference is the Jewish God. Indeed, Bloom goes on to claim that Freud's

infamous reduction of religion to the longing for the father, for the

blessings of paternal authorization, "makes sense only in a Hebraic

universe of discourse, where authority always resides in figures of

the individual's past and only rarely survives in the individual proper"

(RST, 161). This is the thought of "a psychic cosmos, rabbinical and

Freudian, in which there is sense in everything, because everything

already is in the past, and nothing that matters can be utterly new"

(RST, 152).

Read now at JSTOR

Anamnesis of the Visible 2

Jean-François Lyotard

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Anamnesis

Painting struggles, it labors in the strong sense of the word,

that used by obstetrics and psychoanalysis, to leave a trace or to

make a sign in the visible of a visual gesture that exceeds the visible. Such is the paradoxical idea that we need to explore. A double

paradox: first, of a chromatic matter that one cannot see because it

exceeds the visible, and which nevertheless is, if I may say so, already colored. And, then, of a gesture in this matter and of this

matter, and thus also in and of the space-time that it deploys through

the gesture itself –– the paradox, in other words, of a gesture that is

not the doing or not simply the doing of a conscious subject, namely,

the painter. More than anything else, the painter, like the woman or

the analysand in labor, would have to leave open a way through

which something that has not yet happened, a child, one's past, or

in this case a color phrase, and that nevertheless is already potential human life, possible memory or eventual chromatism, can happen. The conscious subject works on itself, with and against itself,

to keep itself open to this eventuality. The pictorial gesture reaches

the eye, thus prepared to be unprepared, as an event. Not because

it would arise unexpectedly, since on the contrary, it will have been

awaited and violently wished for. But it is an event insofar as the

subject giving issue to it did not and does not know what this event

is or of what it consists, so to speak. The painter does not control it.

Read now at JSTOR

Before the Law, After the Law: An Interview with Jean-François Lyotard

Elisabeth Weber

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Elisabeth Weber –– In your book, Heidegger and "the jews", you

attempt to analyze something you call a paradox, or even a scan

dal. You describe it:

“[H]ow could this thought (Heidegger's), a thought so

devoted to remembering that a forgetting (of Being) takes

place in all thought, in all art, in all "representation" of

the world, how could it possibly have ignored the thought

of "the jews," which, in a certain sense, thinks, tries to

think, nothing but that very fact? How could this thought

forget and ignore "the jews" to the point of suppressing

and foreclosing to the very end the horrifying (and inane)

attempt at exterminating, at making us forget forever what,

in Europe, reminds us ever since the beginning that "there

is" the Forgotten?”

You have been attempting for several years now to think this figure

of the Forgotten under several names: the infans, childhood, the

event, the condition of the hostage, to name but a few. If the thought

of "the jews" reminds us that there is a Forgotten, it also introduces the law and a thought of the law, a law that, as you write in

a text on Kafka, inscribes itself "onto a body that does not belong

to it. ...This inscription must necessarily suppress the body as outlaw savagery.”

Read now at JSTOR

Michael Snow's Wavelength and the Space of Dwelling

Michael Sicinski

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In 1967, Michael Snow presented Wavelength, his fifth film, for the

first time. Jonas Mekas has recalled this initial screening of the first

completed lab print, for a private gathering of Snow's friends in New

York City, saying, "I had no doubt we had just witnessed a landmark

event in cinema."' The history of experimental film has borne out

Mekas' belief, and while a viewing of Wavelength today remains

unlike any other cinematic experience imaginable, Michael Snow

is still an artist commonly admired from afar, respected in the United

States but not exactly well-known, and afforded inconsistent attention by recent academic cinema studies. In the brief essay cited

above, Mekas compares Snow to Andy Warhol and laments the fact

that Snow has not attained the same degree of notoriety. The comparison is instructive. While it would be reductive and inaccurate to

call Snow "the Canadian Warhol," he is without a doubt the most

important Canadian visual artist of the twentieth century. Like

Warhol, as well as Marcel Duchamp and Yoko Ono (another of the

century's major artists, equally ignored but for very different reasons), Snow has built a body of work astonishing in its range of

media, encompassing major contributions in painting, sculpture,

photography, and jazz, as well as cinema.

Read now at JSTOR

Early Modern Psychoanalytics: Montaigne and the Melancholic Subject of Humanism

Carla Freccero

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

I. Psychoanalysis and Early Modernity

Whenever the subject arises of the relation between early modernity and psychoanalysis among post-new historicist Renaissance

scholars, one inevitably returns to the early (non)manifesto on the

topic represented by Stephen Greenblatt's "Psychoanalysis and Renaissance Culture."' Indeed, there, in the groundbreaking collection of essays entitled Literary Theory/Renaissance Texts, it was still

a question of the applicability of the 'new' currents of post-structuralist, often French, theory and criticism to the texts of pre-modernity. The most common objection at the time was that the Renaissance

itself did not recognize the terms by which post-structuralist theory

analyzed and interpreted texts and thus that current theory and criticism were anachronistic, which usually meant inapplicable, or at

the very least, 'inappropriate'. New historicism, inaugurally attributed to Greenblatt, came to be seen as the compromise formation

between the parodic poles of a strictly historicist, or explanatory

hermeneutic approach to early modern texts untainted by the modernity or post-modernity of a late twentieth-century interpreter, and

approaches that welcomed the anti-humanist, post-structuralist linguistic and rhetorical 'turns' characteristic of such current theories and interpretive methodologies.

Read now at JSTOR

A Dossier of Papers on Psychoanalysis and Film

“All the Shapes We Make”: The Passenger’s Flight from Formal Stagnation

Homay King

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Antonioni's The Passenger is a film about a British Press journalist

named David Locke, whose most recent project has been to document a rebellion taking place in Africa. The film opens with a series

of images of Locke attempting to get directions and to secure a guide

to the rebel encampment. After his truck breaks down in the desert,

the frustrated Locke returns to his hotel, to discover a man lying

dead in an adjacent room. The man is Robertson, a fellow traveler

from England with whom Locke has become acquainted, and whom

Locke resembles physically to an uncanny degree. In a flash, Locke

decides to trade in his identity for Robertson's, to exchange his

journalist's clothing and equipment for his double's blue shirt and

appointment book.

After a brief trip to London, Locke embarks upon the itinerary

laid out in Robertson's calendar, heading for Munich. In the airport

there, he discovers that a key which was part of Robertson's personal effects opens a locker, in which a packet of diagrams for weapons has been stored. Posing as Robertson, Locke then goes to a

meeting in a nearby baroque church, where he completes Robertson's

weapons deal with a rebel leader named Achebe. Back in London,

Locke's wife Rachel has heard the news of her husband's alleged

death.

Read now at JSTOR

“It Ain't Fittin’”: Cinematic and Fantasmatic Contours of Mammy in Gone With the Wind and Beyond

Maria St. John

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

When David 0. Selznick's 1939 Gone With The Wind (GWTW)

was re-released in Technicolor in the summer of 1998, Rolling Stone's

endorsement urged, "Catch GWTW in a dazzling, digitally re-mastered version." It seems that although 90% of the North American

population has seen the film, and sales of Margaret Mitchell's 1936

novel have been rivaled only by the Bible, still there is something

that the dominant cultural imaginary continues to attempt to master

through the reproduction of this story, some fantasied fugitive who

escapes no matter how many times she is captured on celluloid or

in print. I would like to suggest that the longevity of dominant cultural interest in GWTW may be in large measure attributed to the

appearances of the character Mammy in both the book and the film.

The mammy stereotype may seem archaic, but the continued market success of Aunt Jemima products, as well as the proliferation of

mammy-isms across literary and visual cultural forms, attest to its

continued activity.

Read now at JSTOR

Melancholia / Postcoloniality: Loss in The Floating Life

David Eng

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

I. The Subject of Melancholia

In "Mourning and Melancholia" Freud asserts that a "good, capable

conscientious woman will speak no better of herself after she develops melancholia than one who is in fact worthless; indeed, the former

is perhaps more likely to fall ill of the disease than the latter, of

whom we too should have nothing good to say." More likely to

succumb to the disease than her worthless counterpart, the good

woman, Freud intimates, might indeed be a melancholic woman.

Throughout his 1917 essay, Freud describes melancholia as a debilitating pathology, one leading to "a profoundly painful dejection, cessation of interest in the outside world, loss of the capacity to love, inhibition of all activity, and a lowering of the self-regarding

feelings to a degree that finds utterance in self-reproaches and self

revilings, and culminates in a delusional expectation of punishment"

(244). Here, Freud suggests this melancholic condition might not

be aberrational but normative of 'proper' female subjectivity. Is the

good woman the 'proper' subject of melancholia?

Read now at JSTOR

Response to the Papers of Maria St. John, Homay King, and David Eng

Kaja Silverman

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The three excellent papers included here provide a compelling dramatization both of the heterogeneity of psychoanalysis, and

of its relevance to the issues which most concern us today. Maria St.

John has used Kleinean theory to interrogate the obsession of white

Americans with the figure of the Mammy, and to account for how it

is that we deny our unconscious racial multiplicity. Homay King

has drawn upon Lacanian theory to think about the formal consistency of the ego and its objects, and to fantasize about an alternative subjective aesthetics. Finally, David Eng has turned to Freudian

theory for the purpose of thinking about the unification of Hong

Kong and mainland China, along with the affective coordinates both

of femininity and Hong Kong subjectivity.

Read now at JSTOR

Book Review

“An extreme thought of difference”: Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe's Poetry as Experience

Jeff Fort

A review of Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe. Poetry as Experience. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999).

Read now at JSTOR

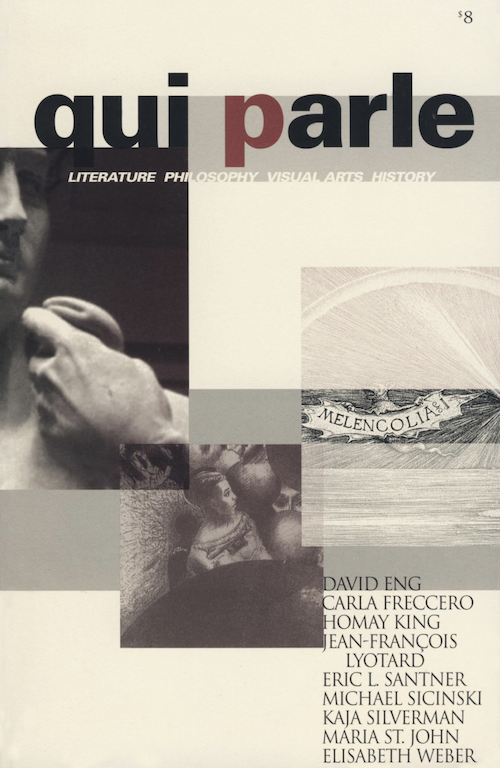

Cover: Details from: Odillon Redon, The breath which leads living creatures is also in the SPHERES, courtesy, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris; and The Raven, courtesy Ottawa National Gallery of Canada. Albrecht Durer, Melencolia 1.

Volume 11.2 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.