The End of Nature: Dossier on Hans Blumenberg

On the Possibility of Creative Being: Introducing Hans Blumenberg

Anna Wertz

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

"The Imitation of Nature," first published in the interdisciplinary journal Studium Generale in 1957, is arguably the most nuanced and ambitious essay of Hans Blumenberg's early career. The

ostensible topic, how man came to think of himself as a "creative

being," leads Blumenberg into a history of philosophical conceptions

of Being and of creation from the Greeks to the present. Extending

outside the confines of the metaphysical tradition into theology, literature, artistic treatises, and technological manifestos, Blumenberg

provides a multi-layered study of humanity's changing attitude toward its own creations, those of nature, and the range of responses to

the long-enduring dictum that art should imitate nature.

Read now at Duke University Press

“Imitation of Nature”: Toward a Prehistory of the Idea of the Creative Being

Hans Blumenberg

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

For almost two thousand years, it seemed as if the conclusive and final answer to the question, "What can the human being, using his power and skill, do in the world and with the world?" had been given by Aristotle when he proposed that "art" was the imitation of nature, thereby defining the concept with which the Greeks encompassed all the actual operative abilities of man within reality — the concept of techne. With this expression the Greeks indicated more than what we today call technology [Technik]: It gave them an inclusive concept for man's capacity to produce works and form shapes, a concept comprising the "artistic" and the "artificial" (which we so sharply distinguish between today). Only in this broader sense ought we use this term we translate as "art." "In general," then, according to Aristotle, "human skill either completes what nature is incapable of completing or imitates nature." This dual definition is closely tied to the double meaning of the concept of nature as a productive principle (natura naturans) and produced form (natura naturata). It is easy to see, however, that the overlapping component lies in the element of “imitation." The task of picking up where nature leaves off is carried out, after all, by closely following nature's prescription, by taking what is inherently given and carrying it out. This interchangeability of art for nature extends so far that Aristotle can say that the builder of a house only does exactly what nature would do, if it were able, so to speak, to "grow" houses. Nature and "art" are structurally identical: The immanent characteristics of one sphere can be transposed into the other. This idea was then established as fact when tradition shortened the Aristotelian formulation to ars imitatur naturam, as Aristotle himself had already expressed it.

Read now at Duke University Press

Metaphorically Speaking: Hans Blumenberg, Giambattista Vico, and the Problem of Origins

Samuel Moyn

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

"To speak of beginnings is always to be suspected of a mania for returning to origins," the contemporary German philosopher Hans Blumenberg comments near the outset of Work on Myth, his monumental tome on the subject of the role of myth in human culture. Evidently surmising that readers might attribute to him just this pathological enthusiasm, Blumenberg moves quickly to disarm this possible misinterpretation of his project. He states categorically: "Nothing wants to go back to the beginning that is the point toward which the lines of what we are speaking of here converge. On the contrary, everything apportions itself according to its distance from that begin ning." A few pages later, he reiterates this hostility to origins and even takes it in a more radical direction. It is not only inadvisable, for Blumenberg, to retrieve the moment of origin. It is impossible: "[T]heories about the origins of myths are idle. Here the rule is: Ignoramibus [We will not know]," he writes. "Is that bad? No, since we don't know anything about the 'origins' in other cases either."

Read now at Duke University Press

Unfamiliar Methods: Blumenberg and Rorty on Metaphor

Anthony Reynolds

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In his review of the English translation of The Legitimacy of the Modern Age, Richard Rorty applauds Hans Blumenberg's monumental work as a vindication of pragmatism. For Rorty, Blumenberg recuperates a positive notion of philosophical modernity as a pragmatic enterprise inaugurated by the pragmatic hero Francis Bacon. While it may come as no surprise that Rorty would offer his praise of this work on the basis of Blumenberg's pragmatic defense of the Enlightenment, his point is more than merely self-serving. It is in fact not altogether false to argue that Blumenberg's project is at times explicitly pragmatic, that the rationality characterizing the modern age is legitimated, in Rorty's terms, as a "pragmatic choice among available tools."

Read now at Duke University Press

From the Theory of Technology to the Technique of Metaphor: Blumenberg’s Opening Move

Rüdiger Campe

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Whereas products of modern science and technology sever themselves from what was there before they emerged, techne, like the ancient techne of rhetoric, seems to be principally concerned with effects that take place within limited frames. Metaphor, for instance, was seen in classical rhetoric and poetics as merely adding to the power or beauty of normal discourse, which the rhetorician was then able to reconstruct in every rhetorical figure. All the more striking is Hans Blumenberg's turn away from his philosophical beginnings in the 1950s, when he was deeply engaged in questioning modern technology, toward a metaphorology at the beginning of the 1960s. The turn to metaphorology signaled Blumenberg's increasing concern with the description and analysis of rhetorical effects in concept-building within epistemological and philosophical traditions.

Read now at Duke University Press

Mass Times Acceleration: Rhetoric as the Meta-Physics of the Aesthetic

Anselm Haverkamp

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Mass times acceleration is the formula defining force and is by implication associated with the law of inertia as defined by Newton's third definition. More than merely staking out an epoch in the history of science, Newton's law has inaugurated an epochal history of the natural sciences. My concern with this topic will be only marginal; my intention here is not to write an essay on the natural sciences, but rather on the history of the category of the aesthetic, or at best the history of knowledge — one that does justice to the cryptic relationship between what, since Baumgarten and Kant, has been called the aesthetic and the surplus (or inertia) of what was available in the development of modern natural scientific research. Allow me to make some preliminary observations on this broad field in order to stake out a claim.

Read now at Duke University Press

Article

Resenting AIDS: Paranoia, Punishment, Performativity

Christopher Peterson

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Recently a close friend of mine submitted to the harrowing exigency of an HIV antibodies test. He had put off taking the test for many months, and glibly explained his procrastination, remarking: "I'm a student, I don't have time to be positive." Since then, I have often thought about the curious logic of his phrase; reflecting on the epistemological turn of the screw, I suppose, he imagined would somehow perform—or bring into being—his seropositivity. For how could he now be positive whereas prior to that knowledge he was not? That is, if he were to test positive, in no way could his seropositivity be understood not to have existed prior to its disclosure. And yet, this anecdote suggests something altogether different: namely, that the knowledge of one's seropositivity is performative—itself infectious. Moreover, such an elision suggests that AIDS discourse has a life beyond the material reality of the virus that implicates it in a vastly overdetermined nexus of biological/discursive production.

Read now at Duke University Press

Review Essay

After Potemkin Politics: On Tom Cohen's Ideology and Inscription

Chris Diffee

A review of Cohen, Tom. Ideology and Inscription: “Cultural Studies” after Benjamin, de Man, and Bakhtin. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Read now at Duke University Press

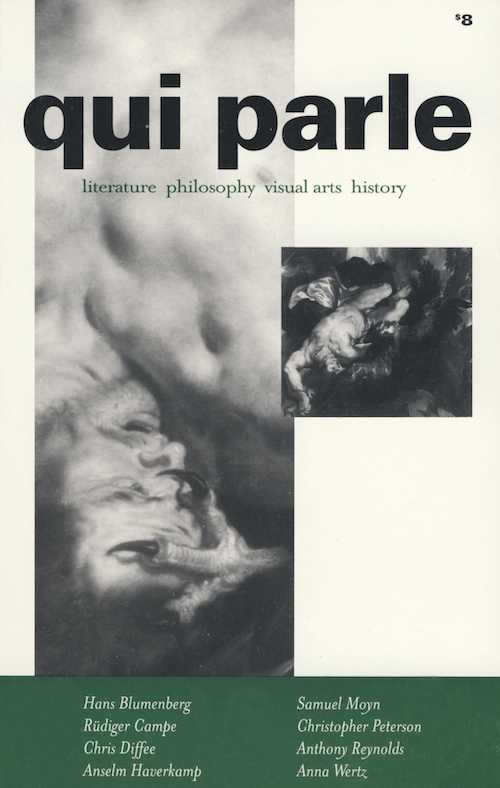

Cover: Details from Peter Paul Rubens, Prometheus Bound, c. 1611, courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Frances Bacon, public domain, courtesy of Princeton University Press.

Volume 12.1 is available at Duke University Press and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.