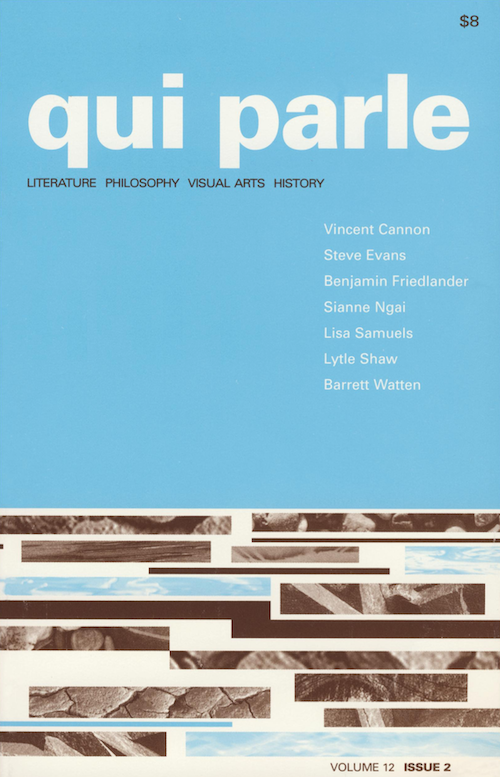

Special Issue on the Poetics of New Meaning, Guest Edited by Barrett Watten

Introduction: The Poetics of New Meaning

Barrett Watten

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The essays presented here are, in related ways, investigations of the poetics of the new, researches into the literary and cultural status of new meaning. The authors are each innovative poets and critics who have weighed in the balance the present possibilities of their work with the claims to innovation of earlier periods, particularly the generation of poets and critics immediately preceding theirs. Committed both to innovation and its historical tradition, what position do they find themselves in? Is innovation still a primary goal, or is the new at this late date a nightmare of precedence, a mere renewal of earlier possibility, or a cataclysmic break? Something of the historical stakes of this question can be measured in our present distance from Charles Olson's epigraph above, which records either a clean or an untidy break with tradition, but one asserted absolutely nonetheless. Writing at the historical dawn of the postwar period, when a new generation of American poets and critics aligned the horizons of their work with an evidently transformed field of cultural possibilities, Olson declares his desire for the destruction of the old world even while he mourns the loss of its stabilities. As an indication of our present moment, Leslie Scalapino's perspective, in this sense, could not be more opposite: any historical break with the past occurs in the lived present as a moment of perpetual return, an unstable inauguration that is at the same time a form of self-shattering where the mind collapses onto the depthless surface of the present. Scalapino's perspective lacks entirely the epochal declaration of Olson's moment; rather, she reinterprets the epochal break as an analytic potential to be found at all points within the habituated orders of the everyday. In these examples, a succession of styles offers an historical index to one of many inversions or reversions of the "tradition of the new.”

Read now at Duke University Press

Articles

Moody Subjects / Projectile Objects: Anxiety and Intellectual Displacement in Hitchcock, Heidegger, and Melville

Sianne Ngai

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

While closely tied to temporal dynamics of postponement and anticipation, however, there seems to be a curiously spatial component to anxiety as well. In psychological parlance, for example, anxiety is typically described as an affective response to a projected, i.e., futural event, but it is also frequently invoked as something "projected" onto others in the sense of an outward propulsion or displacement: that is, as a quality or feeling the subject refuses to recognize in himself and attempts to relocate in another person or thing, usually as a form of naive or unconscious defense. Althusser refers to this kind of projection when describing his psychiatric evaluation in The Future Lasts a Long Time: "In my own case, it is striking that the most well-intentioned doctor in the world . . . projected on to me his own anxiety . . . [and] as a consequence of this projection and confusion, was partly mistaken about what was really happening inside my head. [My] doctor's attention was fixed on a specific anxiety which he passed to me rather than observed in me, thus shifting it from its 'object,' or rather from the absence or loss of any 'object,' to the representation of his anxiety projected on to me" (274, my italics). And yet this account of projection as the externalizing trajectory by which anxiety becomes displaced seems paradoxically internal to Freud's definition of anxiety itself, though never overtly elucidated by him as such. In his attempt to redefine neurotic anxiety, for example, from its initial formulation as "fermented" libido (sexual energy transformed from being accumulated without discharge) to the experience of unpleasurable, endogenous excitations subsequently treated as if they were coming from without, Freud's approach to anxiety shifts from viewing it as an "inside" matter to a matter of the very distinction between inside and outside. This conceptual shift comes to a particular head in Freud's eventual appeal to the experience of birth, an emergence/expulsion par excellence, as "the first experience of anxiety, and thus the source and prototype of the affect of anxiety.”

Read now at Duke University Press

“A World Unsuspected”: The Dynamics of Literary Change in Hegel, Bourdieu, and Adorno

Steve Evans

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The problematic of literary change has engaged every generation of writers and critics since the German Romantics at the turn of the nineteenth century. By virtue of their insistent elaboration within the epoch of capitalist modernity, the questions this problematic renders imperative — how do we identify and account for, and why do we value, formal and semantic novelty (classically formulated in Arthur Rimbaud's demand for "the new — ideas and forms")? on what criteria are necessary and consequential innovations to be distinguished from trivial or superficial ones? what if any temporal rhythms govern the transformative processes at work in the literary field? — present themselves today in forms that are as keenly reflexive as they are richly historicized. Indeed, in accordance with the axiom of intellectual life that paradoxically equates high degrees of historically achieved reflexivity with depletion and exhaustion, it can seem today as though the problematic of literary change has itself passed from relevance. The concept of the "new" appears less a harbinger than a vestige; and in direct proportion to the ubiquity of claims to novelty in technological and commercial domains a silence that can only be taken as deliberate is the only comment many serious contemporary artists, writers, and intellectuals feel the topic merits.

Read now at Duke University Press

A Short History of Language Poetry / According to “Hecuba Whimsy“

Benjamin Friedlander

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The following study, abridged from a much longer work, is an experiment in criticism: a strict rewriting of Jean Wahl's A Short History of Existentialism which faithfully strives, within the parameters established by my source text, to produce a coherent, historically accurate account of language writing. The essay which results is emphatically not what "I" would have written if left to my own devices, hence the pseudonymous attribution. Though worked out with care from the available materials, the ideas and formulations presented here are no more my own than they are Jean Wahl's, which is not to say that I disown them. Sincerity in the Poundian sense — "a man standing by his word" — is simply not at issue. At issue instead is the value of a compositional practice in which criticism is no longer derived from a given set of facts, opinions and interpretive strategies, but is rather the end result of a collision between two historically specific intellectual projects. In "Hecuba Whimsy"'s "Short History," these two projects are existentialism (as succinctly framed by Wahl's post-WWII humanism) and language writing, and they provide her collision with its "immovable object" and "irresistible force," respectively. Yet the crash recorded here was not haphazard. Though a function of violent synthesis, "Hecuba Whimsy"'s final text bears the scar of its construction in a neat seam that runs through every sentence, along the boundary line dividing the essay's form and content. The shape of the narrative, its idiosyncratic style and anachronistic tone, were all appropriated from Wahl. The narrative's substance and theoretical vocabulary were determined instead by the specific character of the work under discussion.

Read now at Duke University Press

Proximity's Plea: O'Hara's Art Writing

Lytle Shaw

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Both in critical studies like his 1959 book Jackson Pollock and in his poems such as "Second Avenue" (1953), "Ode to Willem de Kooning" (1958), and "Far from the Porte des Lilas and the Rue Pergolese" (1958), Frank O'Hara's writing famously blurs the line between poetry and criticism. Rather than draw out the critical implications of these extreme characterizations of Pollock and de Kooning, however, art critics have tended to dismiss O'Hara simply for pushing criticism towards poetry. Here, in its hybrid state, such writing falls into Clement Greenberg's hated category of "pseudo poetry" and Michael Fried's despised "'poetic' appreciation." That O'Hara's critical prose is poetic is certainly a more common observation than the converse claim that his poetry is critical. This is because the assertion that a mode of writing operates critically tends to draw a reasonable question about the terms of its operation, whereas the claim that writing is poetic generally does not. From either side of the equation, though, critics have been less interested in characterizing how and why poetry interacts with other disciplines in O'Hara's work, and what the terms of this interaction might be, than in attacking or celebrating the very fact that it does. Thus, for postmodern critics reacting against Greenberg and Fried, the literal merging of poetry and painting in O'Hara's collaborations with such artists as Grace Hartigan, Larry Rivers, and Jasper Johns has been framed as a subversion of Greenberg's and Fried's pivotal late modernist stances against interdisciplinarity. Insofar as disciplinary specificity becomes modernism's last rallying cry, O'Hara, because he welcomes the interaction of text and image, gets understood as a proto-postmodernist. But what remains contemporary about O'Hara is less the fact of interdisciplinarity than the special functions it takes on in his work, which have everything to do with his excessive and strange descriptions of Pollock and de Kooning.

Read now at Duke University Press

If Meaning, Shaped Reading, and Leslie Scalapino's way

Lisa Samuels

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

This essay concerns new ways of reading poetry, particularly unconventional twentieth-century poetry such as Leslie Scalapino's 1988 book way. Now that poststructuralist theory has articulated a properly skeptical attitude toward Enlightenment ideals of authoritativeness, comprehensiveness, critical accuracy, progress, and objectivity, literary studies has more institutional opportunity to articulate critical practices — I think of them as "practices of theory" — that activate the contingency and changefulness of literary works and of criticism itself. The title of this essay points to a forebear of such practices of theory in William James' concept of "if meaning," and the essay itself will demonstrate a practice of theory that I have called in previous work "deformative criticism" and that I call here “shaped reading.”

Read now at Duke University Press

Review Essays

Spectres of Christ: Love, Christianity, and the Political in Slavoj Žižek’s The Fragile Absolute

Vincent Cannon

A review of Žižek, Slavoj, The Fragile Absolute: or, Why Is the Christian Legacy Worth Fighting For? (London: Verso, 2000.)

Read now at Duke University Press

Volume 12.2 is available at Duke University Press and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.