Articles

The Idea of an Anthropology of Islam

Talal Asad

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

For three decades, Talal Asad's work on the question of religion, and on

the entanglements of this question with the sensibilities of modern life, has

steadily overturned dominant paradigms in anthropology. Critiquing the

textualization of social life, his work has redirected analysis away from

the interpretation of behaviors and toward inquiry into the relation of

practices to what he has termed a "discursive tradition." Asad introduced

this concept in making an intervention in the anthropology of Islam, yet

it has also become important across a number of fields (anthropology,

religious studies, postcolonial studies, critical theory) concerned with ethics and religion in modernity. It was first elaborated in the paper below,

written in 1986 for the Occasional Paper Series sponsored by the Center

for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University. Despite the

essay's significance, it has not circulated as widely as Asad's other writings. Qui Parle is reprinting it in order to make available the particular

arguments that developed this broadly influential concept.

In recent years there has been increasing interest in something

called the anthropology of Islam. Publications by Western anthropologists containing the word "Islam" or "Muslim" in the

title multiply at a remarkable rate. The political reasons for this

great industry are perhaps too evident to deserve much comment. However that may be, here I want to focus on the conceptual basis

of this literature. Let us begin with a very general question. What,

exactly, is the anthropology of Islam? What is its object of investigation? The answer may seem obvious: what the anthropology of

Islam investigates is, surely, Islam. But to conceptualize Islam as

the object of an anthropological study is not as simple a matter as

some writers would have one suppose.

Read now at Duke University Press

Mad Raccoon, Demented Quail, and the Herring Holocaust: Notes for a Reading of W. G. Sebald

J. M. Bernstein

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Creaturely life is a life that is in excess of both biological life and

our life in the space of meaning, between––but in excess of––both

instinct and symbol; creatureliness denotes life as determined by

the drives rather than by emotions, feelings, instincts, or ideas. Although primarily a concept intended to capture a particular possibility and deformation of human experience, in the writings of

W. G. Sebald creaturely life is most perspicuously presented in images of animals who have lost their natural place, lost the possibility of living an animal life in becoming subject to the demands

of culture, subject to forces beyond their control––culture become

force. At the very beginning of Austerlitz, the narrator recalls visiting the newly opened Antwerp Nocturama and watching a raccoon sitting beside a little stream "with a serious expression on its

face, washing the same piece of apple over and over again, as if it

hoped that all this washing . . . would help it to escape the unreal

world in which it had arrived, so to speak, through no fault of

its own."

Read now at Duke University Press

Does Creativity Deny Itself?

Gabriela Basterra

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Since the onset of modernity, as part of the Enlightenment's self

representation of Western culture, artistic creation and the human

imagination have been linked to positive emancipatory forces. Yet

if we look back to what precisely the modern "invention of tradition" recovers as the first work of fiction, Greek tragedy, we find

that the Western self takes as its first self-representation, paradoxically, the denial of the human ability to act: although tragic heroes such as Agamemnon or Eteocles try to take action, their decisions and acts recoil against them with fatal results. Their initiative

is usurped and reversed by an external force, fate, that provokes

their death. Thus it would seem that the human imagination simultaneously enables and thwarts agency. It does so by producing

destructive inventions, such as tragic fate, which in spite of being

themselves created within an artwork––a work of fiction––radically contradict the human capacity for action. This is astonishing.

Should we conclude from this that the imagination denies itself?

Read now at Duke University Press

Derrida's Ouija Board

Christopher Peterson

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In M. Night Shyamalan's The Sixth Sense, the aptly named Cole

Sear (Haley Joel Osment) discloses to his therapist the now-infamous words: "I see dead people." Only at the end of the film does

Malcolm Crowe (Bruce Willis), the child psychologist to whom Cole

confides, finally realize the full implications of what his patient has

been trying to tell him: that Crowe is one of these dead people who

has trespassed the supposedly unbridgeable barrier between the living and the dead. The declaration "I see dead people" thus implies

Crowe's death as the condition of its veracity. How could the psychologist not see, as it were, the possibility that “I see dead people" means "because I see you, because I look at you and tell you

this, you, therefore, are dead"? Cole's words must therefore induce

Crowe to a certain blindness––a disavowal that the film requires

of the spectator by extension––in order for this "surprise" revelation to work. The film counts on the blindness of the spectator to

the possibility that his or her own death is presumed by the child's

revelation. Insofar as the film urges us to see (or not to see) through

the eyes of Malcolm Crowe, we are permitted to pass through the

province of the spectral, at least until we leave the theater to return

to the world of the living, reassured of our self-presence.

Read now at Duke University Press

Sophisticated Ways in the Destruction of an Ancient City

Hanaa Malallah

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

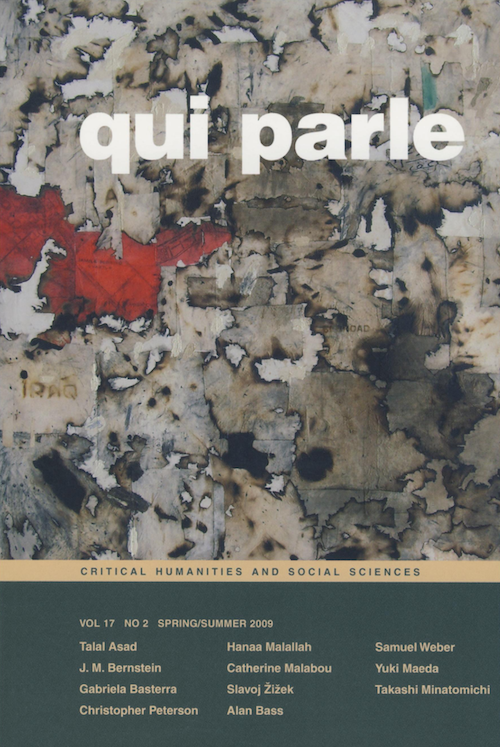

Curatorial Note

Since the 1970s the art of Hanaa Malallah has borne witness to the

ongoing catastrophes that have befallen Baghdad. The most recent

of these: a war with Iran encouraged by the American bloc, then a

war by the American bloc itself, followed by a decade of sanctions

authored by the Clinton administration that brought as much if

not more devastation to Iraq as the war launched by the Bush ad

ministration in 2003. Efforts to give form not only to the damage

suffered by the city in which she lived but also to the collateral

disfigurement of its aesthetic tradition, her works are themselves,

in her words, "ruins," "piles of forms." On the cover of this issue

appears an image of Iraq, New Map/US Map, in which Malallah

reconstructs a cartography of Iraq with pieces of scorched paper,

some of these fragments of faded maps of varying scale, joined by

restorative applications of paint. For Malallah, this is the cartog

raphy that results from the American re-mapping of Iraq, the map

of a "New Middle East" in which orientation is no longer possible.

Read now at Duke University Press

Special Dossier: Past Unconscious: Psyche in the Afterlives of Freud

How Is Subjectivity Undergoing Deconstruction Today? Philosophy, Auto-Hetero-Affection, and Neurobiological Emotion

Catherine Malabou

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Contemporary neurobiological research is engaged in a deep redefinition of emotional life: the brain, far from being a nonsensuous organ, one devoted only to logical and cognitive processes,

now appears on the contrary to be the center of what we may call

a new libidinal economy. A new conception of affects is undoubtedly emerging.

The general issue I would like to address here is the following:

Does the neurobiological approach to affect accomplish a material

and radical deconstruction of subjectivity? I mean: Does neuroscience engage in a more material and radical deconstruction of

subjectivity than the one led by deconstruction itself? Does this approach help us to think of affects outside the classical conception

of auto-affection, of affects that would not proceed from a primary auto-affection of the subject? Does the study of the emotional

brain challenge the vision of a self-affecting subjectivity in favor of

a hetero-affected one?

Read now at Duke University Press

Descartes and the Post-Traumatic Subject: On Catherine Malabou's Les nouveaux blessés and Other Autistic Monsters

Slavoj Žižek

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

If the radical moment of the inauguration of modern philosophy

is the rise of the Cartesian cogito, where are we today with regard

to cogito? Are we really entering a post-Cartesian era, or is it that

only now our unique historical constellation enables us to discern

all the consequences of the cogito? Walter Benjamin claimed that

works of art often function like shots taken on film for which the

developer has not yet been discovered, so that one has to wait for

the future to understand them properly. Is not something similar

happening with cogito: today, we have at our disposal the developer to understand it properly.

In what, then, does this developer consist? What makes our

historical moment unique?

Read now at Duke University Press

Play's the Thing: Jugs Are Us

Alan Bass

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Two babies are feeding at the breast. One is feeding on the self,

since the breast and the baby have not yet become ... separate

phenomena. The other is feeding from an other-than-me source.

Donald Winnicott, Playing and Reality

Play is almost synonymous with deconstructive thought. The inaugural text of deconstruction in America is Derrida's "Structure,

Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences." The importance of play in Nietzsche's thought needs no rehearsal. For

Heidegger too, play is essential––think of the play of the fourfold,

which is part of my topic here. In psychoanalysis play has several

obvious resonances. Melanie Klein invented play therapy for chil

dren. Donald Winnicott is the great theoretician of play. The fort/da scene is a scene of play.

Read now at Duke University Press

On the Japanese Translation of The Legend of Freud: A Dialogue with Samuel Weber Samuel Weber, Yuki Maeda, and Takashi Minatomichi

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The following dialogue developed as a conversation with the

Japanese translators of my book, The Legend of Freud (Stanford:

Stanford University Press, 2005), Takashi Minatomichi and Yuki

Maeda, who suggested that I provide an introduction to their

translation. I asked them if it might not be more interesting for

us to engage in a dialogue based on their experiences in translating the book. I also asked if they might provide me with a brief

review of the history of psychoanalysis in Japan, so that I would

have some context in which to respond to their questions and other remarks. This they did, and the result is a dialogue that was

conducted in English, for my part, and in French for theirs. Since

a text always involves some sort of dialogue with its readers, my

hope was that this would be the best possible introduction of the

book to Japanese readers. I hope that our conversation will prove

of interest to English-speaking readers as well, however different

the universes of discourse may be.

Samuel Weber

Read now at Duke University Press

Cover: Hanaa Malallah, Iraq New Map/US Map, 2008. More info. See also the article by Malallah in this issue.

Volume 17.2 is available at Duke University Press and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.