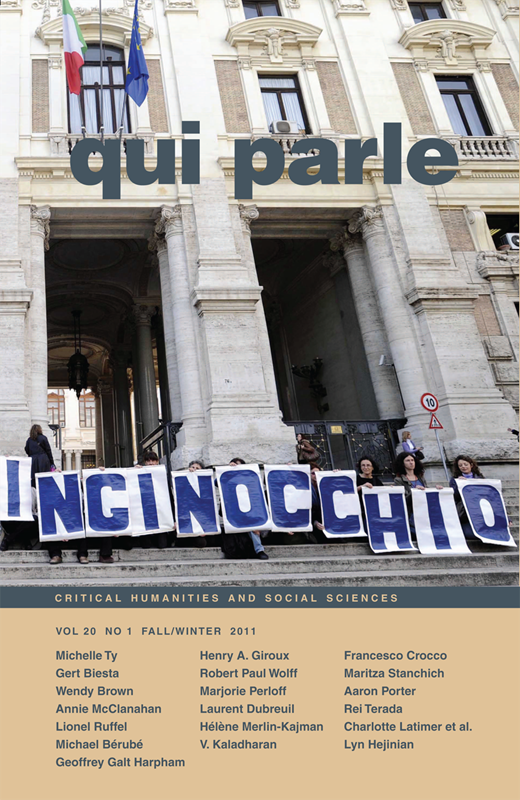

Special Issue: Higher Education on Its Knees

Introduction: Higher Education on Its Knees

Michelle Ty

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

“L’istruzione é in ginocchio” (Education is on its knees), a popular Italian protest slogan goes.1 To think of the present state of higher education by attending to the lineaments of this image might offer a preparatory moment of reflection before we find ourselves, as one inevitably does, knee-deep in the rhetoric of crisis.2 The trope gives bodily expression to the aftermath of what have been largely abstract processes. At times, it would seem that education had been done injury by an uncertain and absent perpetrator. From where do these cuts come? Who has done this? When did this happen? What now?

Read now at Duke University Press

Part I: The University Gone Global

How Useful Should the University Be? On the Rise of the Global University and the Crisis in Higher Education

Gert Biesta

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In many countries around the world there is a sense of crisis concerning the state and future of higher education. This sense of crisis seems to be predominantly connected with the question of resources. Although many universities have seen a steady reduction in their budgets over the past decades, and while many academics have become used to constantly having to do more with less, the recent global financial crisis has brought about much more radical shifts in the funding of higher education—shifts that are not simply financial but also ideological, at least in their implications and often also in their intent. In England, for example, the government has recently decided to withdraw state support from almost all university teaching programs, with the exception of a small number of “priority subjects” (the STEM subjects: science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). To compensate for the impact of this measure, the government is allowing universities to charge students much higher fees, thus shifting the responsibility for the funding of higher education from the state to individual students. While from a North American perspective the actual fees may seem relatively low, they are unprecedented in the English situation, something that was reflected in student protests surrounding the decision making. Scotland is currently still providing higher education to its citizens without charging fees, although university budgets for teaching and research have already been cut and further measures are expected after the elections for the Scottish government in the spring of 2011.

Read now at Duke University Press

Quality and Equality: The Proposed UC Cyber Campus

Wendy Brown

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

These remarks were delivered at the Graduate Student Association’s Forum on the Cyber Campus on October 11, 2010.

I have many thoughts about the differences between the virtual and live classroom. Differences between, on the one hand, classes featuring professors with an avowed point of view, modestly attuned to the abilities of their students, working closely with their GSIs (graduate student instructors), and, on the other, authorless curricula with instructors of record and hundreds of low-paid teaching assistants. Differences between, on the one hand, students in a hushed auditorium, shorn of electronic connections and other distractions, listening to a line of Shakespeare, a measure of Chopin, a principle of physics—taking them apart together to discover the kernel of their brilliance—and, on the other, a student staring at the line, the measure, the principle on a MacBook, perhaps at a Starbucks with e-mail and Facebook portals open, perhaps at home flanked by children whining, bosses calling, friends texting. Differences between, on the one hand, a provocative lecture on the Bill of Rights followed by a discussion with the students about whether the First Amendment can distinguish between speech and action and whether the Second is more fundamentally about individual rights or states’ rights, and, on the other, students contributing to “online threads” on these topics.

Read now at Duke University Press

The Living Indebted: Student Militancy and the Financialization of Debt

Annie McClanahan

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In “Debt and Study,” their manifesto on the politics and ontology of student indebtedness, Fred Moten and Stefano Harvey state that “credit is a means of privatization and debt a means of socialization.” This aphoristic claim is provocatively counterintuitive. First, it rejects the commonplace assertion that credit is the kind of contractual exchange between free equals on which the modern social order depends. Second, it treats credit and debt not as merely two perspectives on the same circular exchange (money passing from lender to borrower and back again) but rather as radically different political subject positions—as positions that are in an antagonistic rather than reciprocal relationship.

In the first part of this essay I take student debt as the occasion to show how destructive credit can be. I suggest that we can see the link between credit and privatization by considering the connection between rising levels of student debt and transformations in speculative financial markets. Far from providing a model for mutuality, obligation, and dependence, these new forms of credit actually set in motion new structures of privatization and impose new types of political discipline. In the second part of the essay I take up the challenge of Moten and Harvey’s claim that the mobile and dispersed “fugitive publics” of student debt make possible new forms of political affiliation.

Read now at Duke University Press

Do Books Have a Place in a Shanghai World?

Lionel Ruffel

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

For those who haven’t yet noticed, there’s a tune everyone’s whistling nowadays, and it’s the tune of rankings and evaluations. We’re evaluating a lot of things, from hospitals to the work of ministries themselves, but from now on it’s the evaluation of universities and of higher education in general that will attract the most attention. And, evaluated in this manner, universities begin to regain their prestige, at long last—not once again—since these rankings and evaluations do not correspond (quite the opposite, in fact) to the glorious image that the French, it seems, would like to have of themselves. No problem! To these rankings (a new genre of human-interest story, quite useful for filling dead space in newspapers), our managers respond with a new battery of assessments, and everybody seems satisfied. Everybody but us, the assessed, such tragic figures—and much more tragic are those among the assessed who happen to belong to the difficult-to-assess discipline of literary studies. No matter how much each of us, according to his or her personal tastes, may jeer at, revolt against, or methodically deconstruct academic rankings (chief among them being the Shanghai ranking), our work becomes more and more influenced by the large-scale procedures of international evaluation. One of these decisive evolutions concerns our relationship with the book.

Read now at Duke University Press

Part 2: Humanities Salvage

The Futility of the Humanities

Michael Bérubé

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In 2003, I published an article in the British journal Arts and Humanities in Higher Education titled “The Utility of the Arts and Humanities.” I gave that paper as a talk at a handful of American universities in the first few years of this century, and at Carnegie Mellon University in 2002 the poster announcing my talk was a modified socialist-realist affair featuring an arm wielding a wrench. It’s a lovely design, well proportioned and not at all heavy-handed (there is no attempt to mimic the Cyrillic alphabet or the high Futurist style), so my wife and I had it framed. A few years later, my older son, Nick, who has a fine eye for graphic design himself, decided to tape an “F” to the side of the word “utility,” and it is his gesture that gives me the title for this follow-up.

For the crisis of the humanities—the legitimation crisis, the crisis of public justification—has now become the crisis of higher education as a whole, and in the second decade of the 2000s it has met up with the structural crisis in state funding. For public universities, the prospects are very bleak: state funding is drying up, and there are no prospects for its replenishment.

Read now at Duke University Press

Why We Need the 16,772nd Book on Shakespeare

Geoffrey Galt Harpham

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Higher education is afflicted by so many threats that it might seem pointless to try to improve the situation by removing just one. But the one I have in mind is connected to others, and if we can take care of the one, others might seem more solvable as well. I am talking about the so-called crisis in scholarly productivity, or overproductivity, in the humanities. According to this argument, warped priorities at colleges and universities have become skewed so that professors are evaluated solely on the basis of their scholarly output rather than on the basis of their teaching, with the result that the educational mission has been sacrificed to research. The commitment to research is particularly destructive, this argument continues, in the case of the humanities, which cannot claim to produce any direct benefits for health, wealth, or national security.

Complaints about “excessive” scholarship are as old as scholarship, which has always seemed, at least to some, gratuitous and distracting. We have the Bible, Shakespeare, and Dickens—why do we need scholarship? We know that the French Revolution, the Civil War, and Winston Churchill existed—what’s the point of hundreds or even thousands of books and articles explaining these subjects yet again? Why waste time with secondary or indirect knowledge about details when we could learn more vital and immediate lessons from reality itself? One of those self-sufficient immortals, William Wordsworth, counseled a friend to leave off his dry studies and learn directly from bounteous nature.

Read now at Duke University Press

Once More, with Conviction: Defending Higher Education as a Public Good

Henry A. Giroux

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

No doubt it will take some of us time to recover from the confident delusion that the global economic recession of 2008 would reveal once and for all the destructive force of neoliberal capitalization, the “vampiric octopus” masquerading as free-market efficiency and neutrality. But once again citizens in the overdeveloped West find themselves puzzling over stories of billion-dollar bonuses for the very business “leaders” who were responsible for the meltdown—an inky black trail of endless zeros from whence red ink once bled out of the gaping wound of an impaled public trust. Four decades of neoliberal social and economic policy have strangulated not only the middle class and the poor but those social institutions organized in large part for their protection—an assault seen most aggressively at all levels of education in the United States. The consequence has been an entrenched political illiteracy (among other forms of illiteracy) across the electorate, which has fueled populist rage, providing an additional political bonus for those who engineered massive levels of inequality, poverty, and sundry other hardships. As social protections are dismantled, public servants are denigrated, and public goods such as schools, bridges, health care services, and public transportation are left to deteriorate, the Obama administration unapologetically embraces the values of economic Darwinism and rewards its chief beneficiaries: megabanks and big business. Neoliberalism—reinvigorated by the passing of tax cuts for the ultra-rich, the right-wing Republican Party taking over of the House of Representatives, and an ongoing successful attack on the welfare state—proceeds once again in zombie-like fashion to impose its values, social relations, and forms of social death upon all aspects of civic life.

Read now at Duke University Press

What Good Is a Liberal Education?

Robert Paul Wolff

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

As my defense of liberal education will be somewhat unusual, drawing as it does on the insights of Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and Herbert Marcuse rather than on Cardinal Newman and John Dewey, it might be useful for me to begin with a reminder of some of the more familiar defenses of liberal education. After reviewing three rationales for undergraduate liberal education, I will turn to what I consider the real justification for the study of our cultural and intellectual tradition.

The first of the three defenses of liberal education is the oldest and perhaps the most traditional: liberal education as the appropriate education for a gentleman. (Not, please note, for a gentlewoman—that consisted of skill with the needle, a bit of music, and the elements of oeconomics, which is to say the management of a household.) A study of the classics, it was thought, would give men of high estate the proper finish, or patina, that would allow them to move gracefully in polite circles. A command of Greek and Latin, like a well-turned leg and a well-filled codpiece, was an evidence of good bloodlines. It was even suggested that familiarity with ancient tongues and literatures might deepen a young man’s understanding of human affairs, although that was, to be sure, more of a tutor’s hope than a realistic expectation.

Read now at Duke University Press

The Decay of a Discipline: Reflections on the English Department Today

Marjorie Perloff

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In 1999, when I first addressed the “Crisis in the Humanities,” I was still optimistic about the future of literary studies. The rapid erosion of support for our disciplines—especially language and literature—was still a few years off: in 2001, most English and comparative literature departments were still engaged in annual hiring. Who would have predicted back then how unabashedly administrators, especially at the big public universities like California, would begin to chip away at literature and language programs? That in 2011 not a day would go by without an announcement that another humanities program has been severely cut or a modern language program quietly eliminated? Faculty governance, moreover, is rapidly being replaced by the new corporate consumer model described, in chilling terms, by Simon Head in a recent essay for the New York Review of Books.2 Head is writing about the British university but the productivity measures he describes certainly characterize US universities as well.

Read now at Duke University Press

A Viral Lexicon for Future Crises

Laurent Dubreuil

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

This point of departure is a point of arrival, or maybe of non-arrival. This might come from a very simple remark. Mastering the code, protocol, or rhetoric of an epistemic discipline confers freedom, confidence, efficacy, strength, and ideas; it also drastically limits what I am seeking to explain, interpret, or describe. While (almost) every scholar pretends to “know” this, its effect on knowledge itself remains largely overlooked. Moreover, the reproductive mission of the “research university” (aka “graduate studies” in the United States) generally works to prevent any serious consideration of disciplinary defectiveness. Throughout the previous century, social-historical imperatives finally made of “interdisciplinarity” a kind of motto for research version 2.0. However, the meaning of “interdisciplinary” fluctuates greatly. In many instances, interdisciplinary scholarship actually points toward a well-organized edifice, where an encounter between divergent perspectives cannot mask the fact that, in the final analysis, power lies in a super-discipline (such as philosophy, history, or mathematics) or a quasi-transcendental discourse (see what is happening with cognitive science or even “theory”). Another version of the concept is closer to a reasoned practice of multidisciplinarity, providing different, though plausibly complementary, approaches to similar phenomena. In both cases, a certain ideal of polymathy is at stake, and this ideal is certainly more appealing to me than the celebration of epistemic over-specializations, or the praise of expertise.

Read now at Duke University Press

Can We Save What We Have Destroyed? Transmitting Literature

Hélène Merlin-Kajman

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

“To save” (sauver): in recent years, this verb has become pervasive. We need to save our planet, animal species on their way to extinction, cultures and languages menaced by globalization. But we also need to save schools, writing and literature, research, the university, and the humanities themselves. All told, we need to save humanity, nature and culture alike. This strange panic betrays a strange unreadiness. Rescuers perform their work of “saving” during disasters and emergencies, and especially during accidents. Thus, we say, “We have to save the furniture.” And, “Women and children first.” Through such rhetoric we figure our future only in terms of life itself, of human beings and things we need for our survival. The task we keep giving ourselves is a radical one: that which we cannot save will disappear or die. It will not transform itself into something else, it will not continue becoming. A catastrophe—be it political, such as a genocide, or natural, such as a tsunami—has suddenly forced history into step with itself. We assume that we are at fault, that to achieve salvation—salvation and rescue by now are meshed together—we need to make amends.

But can education, can teaching, be part of this troubling worldview? Do they, too, need to be saved?

Read now at Duke University Press

Part 3: History on Regional Grounds

From Meditative Learning to Impersonal Pedagogy: Refl ections on the Transformation of an Indian Gurukula

V. Kaladharan

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

For centuries, highly evolved Indian art forms like kathakali dance-theater and kutiyattam theater were fostered by the sophisticated tastes and means of feudal patricians. At the turn of the last century, the hoary heritage of Indian arts had to seek space in the public sphere consequent upon the apathy of the elites and the gradual but decisive breakdown of the feudal system. Lest the aesthetically nuanced dance and theater traditions of India become destitute, luminous poets and exponents of culture made a deliberate attempt to link them with Indian nationalism, inaugurating a period of cultural renaissance in the early twentieth century. They laid emphasis on Indians rediscovering themselves in terms of native identities implicitly represented by classical arts. Their efforts resulted in the public patronage of classical arts and ensured their continued existence.

Read now at Duke University Press

Contesting the Manufactured Crisis of Public Higher Education at CUNY

Francesco Crocco

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Chanting “Education is a right! Fight! Fight! Fight!” a coalition of students, faculty, and staff from the City University of New York (CUNY) staged an act of peaceful civil disobedience at a CUNY Board of Trustees meeting on November 22, 2010, shortly after the board passed significant tuition increases for the spring and fall of 2011. With a huge fiscal crisis looming, New York governor Andrew M. Cuomo and New York City mayor Michael R. Bloomberg called for austerity budgets that include broad service cuts, layoffs, and givebacks from public-sector unions. The tuition hikes are a direct result of these measures. Proponents of the cuts argue that an austerity budget is necessary to balance a budget that unions and public services have purportedly placed in the red. But the truth is otherwise. The fiscal crisis afflicting the city and state is a manufactured crisis caused, above all, by a crippling system of regressive taxation that serves the wealthiest individuals and corporations. This system has bankrupted the state and paved the way for the fast-track privatization of CUNY and other public services.

Read now at Duke University Press

A University Besieged: Initial Impressions of a Student Strike

Maritza Stanchich

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

A widely supported student strike shut down ten of eleven campuses of the University of Puerto Rico (UPR)—which then had 65,000 students and 12,000 employees, including 5,000 professors— for two months last April, May, and June. That strike ended with an accord since broken by the administration, with only one gain remaining: the restitution of canceled tuition waivers, enjoyed broadly by students in sports, bands, honors programs. But the accord also promised to negotiate a new $400 fee, postponed its imposition at the time, and also guaranteed no summary suspensions of student strike leaders. Instead, Puerto Rico’s pro-statehood and Republican governor, Luis Fortuño, fast-tracked four new appointments to the Board of Trustees to do his bidding; his chief of staff publicly called the accords “nothing but paper,” and both publicly vowed to kick out leftists from the UPR. An $800 student fee was announced for January, to be $400 thereafter, though no one can say for how long. Amid growing unrest, a few government-scholarship and work-study programs were announced. Those who recognize the parallels to the University of California in the 1960s and 1970s, where then governor Ronald Reagan instituted fees to destroy the social mission of that premiere institution, suspect the student aid is meant to ease the impact not of the $800 but of the fee as an instrument to privatize the institution in the long term. Students called a strike in a student assembly that made quorum, though some question the legitimacy of the assemblies in part because a majority of the student body, including politically moderate sectors, doesn’t widely participate. The night before the renewed strike was to begin in December, with just three other campuses also staging walkouts this time, the administration demolished gates to the main Río Piedras campus and hired a private firm, Capitol Security, for $1.5 million instead of using its own unionized campus security guards.

Read now at Duke University Press

Student Unrest, University Unrest: The English Gamble with the Future of Higher Education

Aaron Porter

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The year 2010 has perhaps been the most significant of any period in the history of English higher education. A year that began with an Independent Review into University Funding and Student Finance chaired by multimillionaire former BP chief executive Lord Browne of Madingley ended with the greatest student unrest for decades, an unprecedented retrenchment of state funding, the abolition of state involvement in the arts, humanities, and social sciences and the trebling of undergraduate fees to £9,000, making England the most expensive place to attend public university in the world.

As president of the National Union of Students (NUS) in the UK, I have found this to have been perhaps the toughest period in living memory to represent the views of students to the government, university leaders, and the general public, as disappointment quickly turned to anger at the prospect of such a seismic shift in our higher education landscape.

Read now at Duke University Press

Part 4: A Little Thing Called Resistance

Out of Place: Free Speech, Disruption, and Student Protest

Rei Terada

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In Political Spaces and Global War, Carlo Galli suggests that demand for the “positive ‘freedom of’ speech and criticism” is created by the modern state form’s neutralization of domestic political space. “The neutralizing action of State sovereignty,” he writes, “relegates political energies . . . to the Subject’s interior in order to render them politically inoffensive.” The state’s neutralization of public space encourages the development of interior space, thus creating “the Subject’s initially secret conscience.” As Galli sees it, since the early-modern period the state has enabled the idea of such an “inner reserve.” “This situation,” he continues, then “quickly gave rise to a new demand and aspiration” to liberate these interior thoughts.

What is interesting in this sketch of the genesis of “free speech” is that the movement of state repression seems to bring about a lasting elevation of “speech and criticism” among “political energies” of a previously undifferentiated kind. “Political energies” that are unspecified at the beginning of Galli’s description go verbal in order to go underground—they are translated into a form that can survive mentally—only to reemerge at the end of the cycle, still verbal, as a newfound concern for “freedom of speech and criticism.”

Read now at Duke University Press

Creative Subversions: A Politics beyond Representation in the UK

Charlotte Latimer, Christopher Collier, Jaideep Shah, Katherine Burrows, Matthew Woodcraft, and Saoirse Fitzpatrick

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

This statement was written by students from the University for Strategic Optimism in December 2010, during the national student protests that unfolded as a response to the cuts to education and welfare and the unjust restructuring of the UK economy. The article voices the solidarity not only among students but also among all people(s) in Britain who will be negatively affected by the austerity measures of the British government.

Britain was not at a crossroads: before us there did not lie routes from which to choose; rather there existed space to command, to commandeer. The student uprisings were always about much more than cuts; students stood up without hesitation, and still stand against the eviction of democracy from politics and the simultaneous eviction of people(s) from public space.

The illusionary integrity of British democracy means little in the face of a controlling minority that cannibalizes revenue from the country’s lands and extends its parasitic operation through the expropriation of citizens’ tax into a system of private wealth. Its formal inauguration started with the Magna Carta; today the erosion of public agency and public space has found a bedfellow with neoliberalizing tropes of governance.

Read now at Duke University Press

Wild Captioning

Lyn Hejinian

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

What follows is an attempt to address an unruly array of ideas and experiences related to a rough triad of concerns and involvements:

The first component of this triad I’ll cite is the rapidly escalating crisis confronting public education and, more generally, all sectors of the public sphere. This crisis has come to a head in a number of places throughout the world, including, and somewhat early on, in my home state of California, where severe cuts to budgets for public education have been “necessitated” by a large-scale economic downturn. This crisis, brought on by factors within capitalist investment strategies, has been manipulated to justify a capitalist takeover of the public sphere, and especially education, which is seen as a potential site for new investment, and hence profit-making, opportunities. The first victims of the privatization effort are those that remain public. The result is what might be called third-world conditions in K–12 classrooms (though it should be noted that, as soon as development has made any notable progress in nations in the third world, one of the first areas to receive increased funding and other kinds of support is education), and enormous tuition increases (the University of California’s tuition was increased by 40 percent in 2010) coinciding with a radical downsizing of all three of the state’s public higher educational systems (community colleges, state universities, and the UC, with its ten campuses). The University of California is being persuaded by the business leaders who serve as its governing Board of Regents to restructure itself along corporate models; efficiency is the watchword of the moment.

Read now at Duke University Press

Cover: Simona Granati, “Education Is On Its Knees.” An image from the student protests in Italy. More info.

Volume 20.1 is available at Duke University Press, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.