Special Dossier: Affect Theory

Affect Theory Dossier: An Introduction

Marta Figlerowicz

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

There is of course no single definition of affect theory. In one of its incarnations affect theory builds bridges between the humanities and biology or neuroscience. In another it looks back to Søren Kierkegaard and Baruch Spinoza (among others) to refresh our definitions of subjectivity. Some affect theory defends the therapeutic value of embracing unpleasant feelings such as shame, sadness, or loneliness. Its other branches highlight “ugly feelings” (to use Sianne Ngai’s phrase) as sources not of self-knowledge but of social critique. Affect theory can be a sociology of accidental encounters. It can be a psychoanalysis without end, both in leaving no stone unturned and in not caring to achieve a stable outcome. Affect theory can also refuse psychoanalysis and try to make feelings speak for themselves, as if they will best do so if the conscious mind does not interfere. Stylistically, it has encouraged intensely personal scholarship as well as scholarship that tries to do away with personality altogether.

Read now at Duke University Press

Following Generation

Catherine Malabou

Translated by Simon Porzak

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

You’re reading Autumn Crocuses, that Apollinaire poem. You didn’t notice anything special, you didn’t see anything, you passed right by it. There is, in lines 10–11, a small mystery. This mystery is held in the little phrase that runs: “autumn crocuses which are like their mothers / Daughters of their daughters.” Now admit that you’ve never asked yourself what this could really mean, these “mothers / Daughters of their daughters.” You’re going to do just that right now, you’re going to ask yourself that question now. Now? Yes, now, which is to say, afterwards.

Following in his footsteps, after him, “he” being Lévi-Strauss, one of the first to have felt the need to investigate, concerning the Autumn Crocuses, the mystery of “A Small Mythico-Literary Puzzle” (a text published in The View from Afar). Lévi-Strauss does not present a reading of Apollinaire’s entire poem, but only of this “detail that has remained enigmatic to commentators. Why does the poet equate with autumn crocuses the epithet mères filles de leurs filles (‘mothers daughters of their daughters’)?” You’re about to discover this enigma, after Lévi-Strauss.

Read now at Duke University Press

Skin, Flesh, and the Affective Wrinkles of Civil Rights Photography

Elizabeth Abel

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

If we needed confirmation of our ongoing investment in the civil rights movement and the visual media that brought its local confrontations to a national audience, For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights, a summer 2010 exhibit at the International Center for Photography, provides a vivid example. Drawing its title from Mamie Till’s heroic insistence on an open coffin for her brutally murdered son and from the determination of African American photographers and newspaper editors to make the shocking image of Emmett Till’s face visible to the public, the exhibit and its accompanying volume powerfully affirm the role of the visual media in bringing racial violence into public view. Simultaneously and less explicitly, however, the volume also illustrates how much more vexed this role is than the language that affirms it, for the horrific photograph to which the title refers does not—indeed could not—accompany the title on the cover. Instead, the image is discreetly positioned at the volume’s interior.

Read now at Duke University Press

Affect in the End Times: A Conversation with Lauren Berlant

Lauren Berlant and Jordan Greenwald

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Lauren Berlant, George M. Pullman Professor of English at the University of Chicago, is renowned for her work on collective affect, sentimentality, fantasies of citizenship, and feminist and queer theory. In honor of her new book, Cruel Optimism, I asked her to help us make sense of a number of artifacts from the contemporary archive, all of which attempt to mark, in some way, the end of an era—historical, political, theoretical, or otherwise. What follows is a conversation that foregrounds not only the affective dimensions of the contemporary moment but also the circumscription of forms of togetherness by what she calls the “austere imaginary” of the American political sphere. Finally, it probes the question of what role affect theory might play in the re-imagination of social and political life.

Read now at Duke University Press

A Nice, Clean Space for a Panic Attack: Notes for Cara Benedetto

Suzanne Herrera Li Puma

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Cara Benedetto often speaks of her work in the language of encounter: sometimes a handwritten note, sometimes a list, sometimes a photograph with writing on its surface. These textual encounters set up a confrontation with the spectator by means of the text’s “self-reflexive voice,” a voice that contains a critical turn even as it engages in an apparently straightforward form of dialogue and address. The materials Benedetto employs to set up such encounters are primarily (but not exclusively) the materials of language itself, scraps of everyday communication: receipts, fragments of conversation, text messages, letters, informational posters. Benedetto appropriates the syntax and rhetoric of these communicative forms and stitches her textual inventions into all manner of paper, book, photograph, video, and sculptural object. Speaking with wit, sarcasm, or deliberately flat-footed prose, Benedetto’s texts underline the stubborn exclusions, assumptions, and fraught social relationships embedded in the discourse(s) that they critically mimic. But these texts also recast their original material with a degree of opacity, so that the language they ventriloquize becomes as disorienting as it is engaging.

Read now at Duke University Press

Body Bags

Cara Benedetto

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Who let in the rain.

Everything in my apartment is a body bag.

The bugs can’t get there, like when id drown myself hoping to get rid of it.

Get rid of the bugs in my hair while my mom watched from the shore. And my dad said a week later, one weaker late, that your hair holds onto oxygen. That you can’t kill bugs like that.

The Oxygen Affect is the name of a movie I made in my dreams. It consisted of a man holding a woman captive in a womb. he’d pump it full of oxygen so that she slept all the time and then he’d visit her to make love, by lubing himself up and traveling through the tubes.

She was me. She was lovely and nude and exhausted. She didn’t care that he was sidled up next to her while she slept in her wet.

Im pretty sure I made it in reaction to “the human centipede,” a film where a doctor attaches travelers by their intestinal tract but never really gets that far. I don’t think.

Read now at Duke University Press

Considering the Desire to Mark Our Buried Nuclear Waste: Into Eternity and the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant

Andrew Moisey

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Perhaps it is reasonable for the Finns to worry that in tens of thousands of years, after no one left on earth speaks any known language, someone will be trodding through their frozen forest and exhume, half a kilometer beneath its granite bedrock, all the poison they hid there. This will be radioactive waste from Olkiluoto Nuclear Power Plant, an industrial park that quietly puffs away alongside the beautiful west coast of Finland. The poison from Olkiluoto will be lethal for a hundred thousand years, roughly twice as long as humans have existed, suffering at the hands of the gods for Prometheus’s igneous discovery and Epimetheus’s mishap with Pandora’s jar. A thousand centuries is mythical time, and as such no one can really be expected to rationally solve a problem ordained to occur within it. Into Eternity (2010) is Danish film-maker Michael Madsen’s recent attempt to meditate on just such a problem: how to remind the next four thousand generations not to dig beneath the Finnish forest floor.

Read now at Duke University Press

Unctuous: Resentment in David Copperfield

Joseph Litvak

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Near the end of David Copperfield, when David has become almost as successful an author as the one who wrote this novel, his aunt Betsey says to him: “I never thought, when I used to read books, what work it was to write them!” David replies: “It’s work enough to read them, sometimes.” Betsey misses her cue here, but Mr. Omer, the merry undertaker, has earlier paid David the compliment for which his humble “sometimes” fishes:

“And since I’ve took to general reading, you’ve took to general writing, eh, sir?” said Mr. Omer, surveying me admiringly. “What a lovely work that was of yours! What expressions in it! I read it every word—every word. And as to feeling sleepy! Not at all!”

(674)

Nothing like a reader who doesn’t feel sleepy at all to betray a novelist’s fear of overstaying his welcome—except, perhaps, the novelist’s fretting, like Dickens’s in his preface to David Copperfield, about the “danger of wearying the reader whom I love” (9).

Read now at Duke University Press

Hate as a Passion of Being

Massimo Recalcati

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

“Instincts and Their Vicissitudes” distills Freud’s theory of the genealogy of hate. Here hate does not appear merely as one possible destination of the drives. On the contrary, when, like Plato in his recounting of Aristophanes’ myth of Eros, Freud undertakes to account for the “origins” of the subject through a sort of genesis myth, he assigns hate a fundamental role.

The first phase of Freud’s myth—like that of Plato’s myth of the androgyne, which Freud himself will recall explicitly in Beyond the Pleasure Principle—is one of indifference, in which the subject is a closed One, indifferent to the external world. (It is not by chance that images of cells, shells, and autotrophism, or self-nourishment, recur so frequently in Freud’s work, pointing to the originarily autistic condition of the subject.) This phase is characterized by a sort of substantial solipsism, one that seems to exclude a priori every trace of the Other. The subject thus first emerges as a closed One for whom, in this first phase, the object has no exteriority. Freud defines the undifferentiated and indifferent status of the subject in this phase using the expression “original reality-ego.” This “original reality-ego” should not be confused with the “final reality-ego,” which is secondary with respect to the “original” and which anticipates the instatement of the reality principle as articulating the difference between the internal and the external.

Read now at Duke University Press

Translation

Versographies by Dmitri Prigov: Introduction

Kristin Reed

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

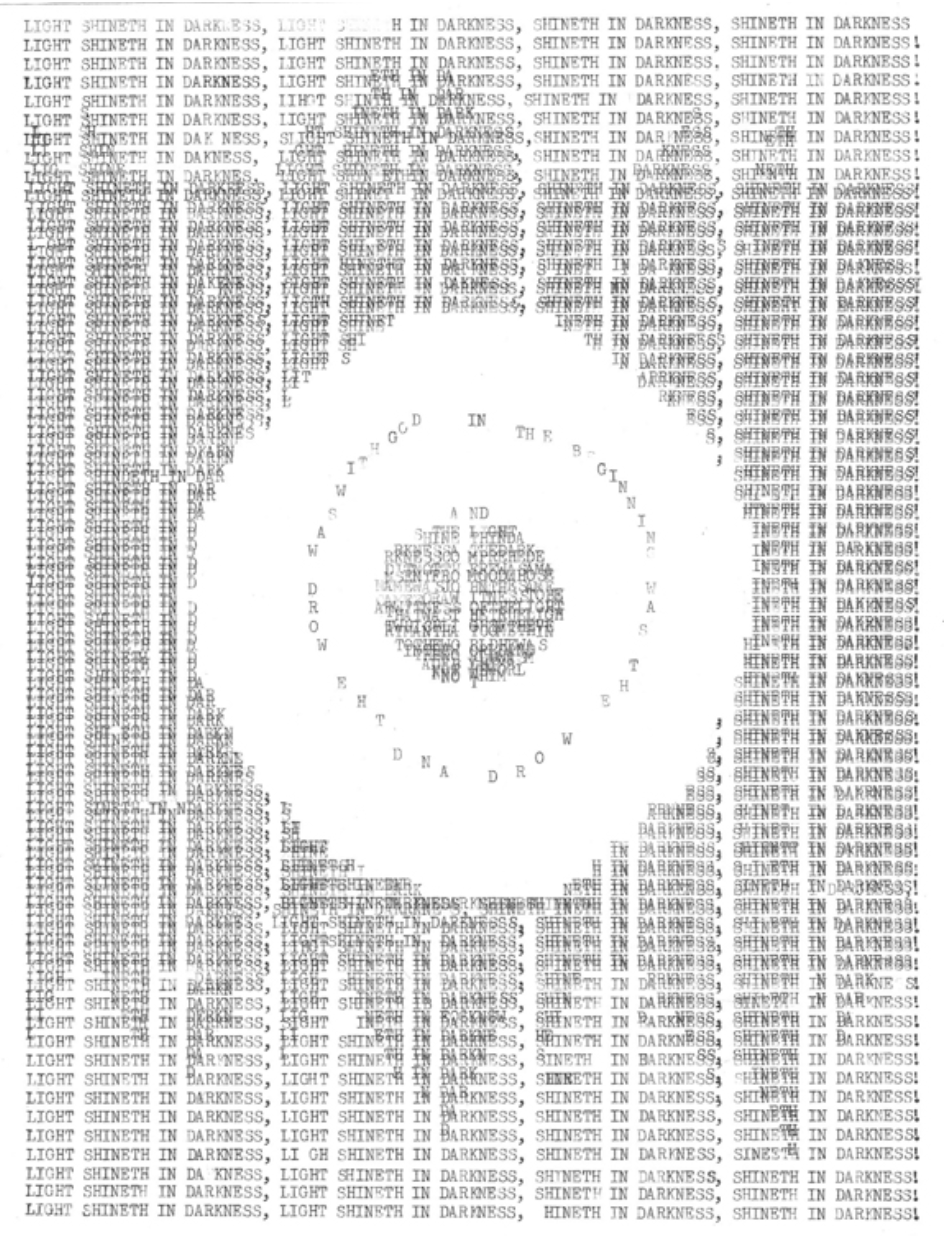

Artists’ books are nothing new, nor is the use of text as visual performance. From Apollinaire’s Calligrams to Igor and Svetlana Kopystiansky’s gallery installations, the West has examined and reexamined literary culture as a visual object through publishing houses, performances pieces, and galleries. Perhaps at the head of this list of craftsmen and poets belongs Dmitri Prigov, Russian author, artist, and purveyor of the perplexing. Prigov began his career as a sculptor, quickly adopting text as an essential medium to his work. An early poet and public art promoter, Prigov belongs to that generation of Russian artists who emerged in the 1970s to challenge the restrictive environment of the late Soviet period. Prigov’s printable work, like that of many of his contemporaries, was disseminated through underground and overseas publishing; it continued to flourish abroad after perestroika and into the twenty-first century.

Read now at Duke University Press

Versographies: A Selection

Dmitri Prigov

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Read now at Duke University Press

Articles

Nietzsche’s Cruel Messiah

James R. Martel

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, in the chapter called “On Redemption,” Nietzsche offers us a vision of a prophet who, coming upon a group of afflicted people, is asked, like Jesus, to heal them:

When Zarathustra crossed over the great bridge one day the cripples and beggars surrounded him and a hunchback spoke to him thus: “Behold, Zarathustra. The people too learn from you and come to believe in your doctrine; but before they will believe you entirely one thing is still needed: you must first persuade us cripples . . . You can heal the blind and make the lame walk; and from him who has too much behind him you could perhaps take away a little . . .”

Read now at Duke University Press

The Career of Living Things Is Continuous: Reflections on Bergson, Iqbal, and Scalia

Donna Jones

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

It is the forgotten war, but still the watershed event of modernity. The Great War was a catastrophic shock to world civilization. The rationalization of slaughter raised the question of what value Western civilization actually placed on life, but the fascist reaction to the horrors of World War I also gave new meaning to life and identified it with death. Only some responded to the carnage with calls for healthy and sensuous living—calls to limit nicotine or alcohol use, to wander in nature, and to display the naked body. But in Germany the intense lived experience of the battlefield formed the basis of a new Kriegsideologie. The German Erlebnis captures this fusion of life and experience. To live meant to live life dangerously. Ernst Jünger’s war writings explored the psychodynamics of extreme lived experiences (echoing all the way to Katheryn Bigelow’s Hurt Locker). We also find an increasingly strident irrational commitment to the vitality of the nation, predicated on the racist destruction of life that is weak. Life either had to grow or die out. But life could only grow through death.

Read now at Duke University Press

Mining the Tropics: Burton’s Brazil and the History of Empire

Betina González-Azcárate and Joshua Lund

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Captain Richard Francis Burton, in collaboration with the scholar Dr. James Hunt, inaugurated the Anthropological Society of London in 1863. Decades later, Burton would describe the project as a forum for the frank discussion of the sexual practices of savages, free from the obscenity laws that could regulate more popular media. A review of the Society’s own scholarly papers, however, shows a slightly different founding concern. With few studies on sexuality, the Society was an organization more explicitly dedicated to contemplating the question of human origins.2 Both the antiquity and the future of the human race, and the question of its role in nature’s plot, were mysteries addressed by the Society.3 But its guiding agenda was to advance the polygenist thesis, the idea that human beings are the result of multiple, local creations and that the descendants of these local families can be divided up into contemporary species. In short, polygenesis proposed that African man and European man are different animals altogether.

Read now at Duke University Press

Cover: Safir Abidi, Landscape of Thorns, 1991. Concept by Michael Brill.

Volume 20.2 is available at Duke University Press, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.