Special Issue: Human Rights between Past and Future, Guest Edited by Zachary Manfredi

Recent Histories and Uncertain Futures: Contemporary Critiques of International Human Rights and Humanitarianism

Zachary Manfredi

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Human rights remain objects of passionate political attachment and endless theoretical speculation. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that one finds so many references to them in the context of contemporary social movements fighting against austerity politics and corporate power. One need only glance at the websites of various Occupy Movement groups to see statements and declarations to this effect: slogans like “Human Rights, Not Corporate Rights!” and demands to “apply principles of human rights” and even create a “Department of Human Dignity—instead of Homeland Security.” Indeed, in 2011 International Human Rights Day served as a powerful rhetorical focus for Occupy assemblies who held up the social and economic rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a contrast to the “corporate rights” recently reaffirmed in the 2010 US Supreme Court case Citizens United.

For some theorists, however, the resurgence of left political movements in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis foretold the death of a post–Cold War politics of international human rights and humanitarian interventions.

Read now at Duke University Press

The Predicament of Humanitarianism

Didier Fassin

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The 2010 earthquake in Haiti provoked a spectacular wave of humanitarianism, especially in the United States, where sympathy for the victims gave rise to the mobilization of a considerable amount of private donations as well as public resources. President Barack Obama solemnly declared less than forty-eight hours after the event that the Haitian people would not be “forsaken” or “forgotten.” Exhibiting what the New York Times then described as “one of the sharpest displays of emotion of his presidency,” Obama evoked the suffering they had endured “long before this tragedy” and announced he would commit five thousand troops, $100 million, and “more of the people, equipment and capabilities that can make the difference between life and death.” Certainly, this empathy was a message sent to the nation: there was a remarkable contrast with his predecessor’s indifference to the victims of Hurricane Katrina. And obviously, this generosity was not exempt of international considerations: after the interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq he had inherited, it was time to give the world a different image of the country. As he phrased it: “This is one of those moments that calls for American leadership.” Many people around the globe, and in Haiti, probably shared this view that for geographical as well as historical reasons, the United States should lead the emergency and reconstruction process on the devastated island. A few dissonant voices were heard, however, and four days later the French minister of international cooperation, backed by Doctors without Borders, bitterly complained about the difficulties encountered by non-US humanitarian workers, as priority was given to the arrival of US troops by airport authorities in Port-au-Prince: “This is about helping Haiti, not about occupying Haiti,” Alain Joyandet undiplomatically declared in reference to the role played by the United States in Haiti during the first half of the twentieth century.

Read now at Duke University Press

Political Ends, Historical Overtures: A Discussion of Samuel Moyn’s The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History

Human Rights Regimes and The Last Utopia

Jason Frank

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Human rights has been proclaimed the hegemonic normative discourse of our time—the “only political-moral idea that has won universal acceptance”—but as the following exchange vividly demonstrates, the history of human rights ascendance and its contribution to emancipatory politics is sharply contested. In part, the controversy springs from the very different forms of politics and governance that have taken shape around the discourse of human rights over the past half century: the contours of different human rights regimes. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948, for example, provided an international legal framework for adjudicating state atrocities like those committed by the Nazi regime during World War II. During the 1980s, human rights were invoked by protesting citizens themselves urging the democratic transformation of authoritarian regimes. Closer to our own time—in the “age of terror”—human rights has become the ruling norm of global security politics, authorizing international economic sanctions and state military interventions, and spawning the parallel governmental discourse of the “Responsibility to Protect”. Most recently, human rights were democratically mobilized once again in the revolutionary transformations of the Arab world.

Read now at Duke University Press

Human Rights and the Material Making of Humanity: A Response to Samuel Moyn’s The Last Utopia

Pheng Cheah

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Samuel Moyn has written a provocative history of human rights that seeks to reveal their true origins in the political climate of the 1970s, where the disillusionment with anticolonialism and communism led to the need for an alternative universalism—namely, the moral utopia of human rights that transcended the contaminated politics of state regimes. As I understand it, one of the main aims of this true history of human rights is so that we can understand both the limits of this utopian vision as determined by its original historical function and the contemporary viability of this vision when current conditions have changed. Writing the true history of something requires that we first determine what that object truly is. I want to look first of all at how Moyn delimits the object he calls “human rights” through a series of demarcations and exclusions. Moyn characterizes human rights conceptually as the liberties of individuals. The true object of Moyn’s history, however, is a fair bit narrower than this already narrow concept of human rights. It is not this concept of human rights as it was articulated in the 1940s and codified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) but rather a subsequent modification whereby human rights are regarded as having a transcendent quality insofar as they should be protected across the boundaries of territorial states. More specifically, it is this modified concept in its wide dissemination in the 1970s: its adoption as a slogan by social movements and its taking root in popular public imagination. In other words, the human rights Moyn is concerned with is a construction of collective public psychology or the popular imagination that saw human rights as an alternative utopia.

Read now at Duke University Press

Whose Utopia? Human Rights, Development, and the Third World

Antony Anghie

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In this provocative and stimulating book, Samuel Moyn boldly states that his intention is to provide a “true history of human rights” in order to “confront their prospects today and in the future.” Moyn’s basic argument is that international human rights is a relatively new invention. Whereas other histories have insisted on seeing human rights as a manifestation and refinement of a set of ideas that could be traced back to natural law and the French and American Revolutions, Moyn insists that it was not until 1977, when Jimmy Carter embraced human rights, making it an integral part of US foreign policy, that international human rights law emerged in its distinctive modern form. In pursuit of this project, Moyn outlines a non-teleological reading of human rights that focuses on the “real conditions for historical developments” that led to the emergence of modern human rights law. He explores how human rights became the central language of moral authority for the expression of international idealism and the management of world affairs. He seeks to distinguish between human rights and other “distinctive globalisms and internationalisms”. Further, and most interestingly for me, Moyn argues that this modern version of human rights emerged in the context of what he asserts was a “crisis of utopianism”.

Read now at Duke University Press

Moving beyond False Binarisms: On Samuel Moyn’s The Last Utopia

Seyla Benhabib

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Rarely in intellectual history has a concept fired the imagination of scholars across disciplines as divergent as law, philosophy, history, and cultural studies during the same period of time. But this is exactly what has happened with the concept of “human rights” in the last two decades. While it may be plausibly argued that the law could hardly ignore the concept—since it is a cornerstone of the modern system of the rule of law—it is nonetheless surprising that in political science and political theory, interest in human rights had waned radically after the late 1960s and was not revived until quite recently. Under the triple attacks of Marxism, some variants of feminism, and the charge of ethnocentrism levied by postcolonial theory, human rights had largely disappeared from view. Even John Rawls’s monumental work A Theory of Justice (1971) did not lead to a revival of this concept. Throughout the 1970s, Ronald Dworkin’s contributions remained nearly alone in urging all “to take rights seriously.” This has changed radically.

Read now at Duke University Press

The Continuing Perplexities of Human Rights

Samuel Moyn

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

I welcome the chance to engage with the readings of my book by these three preeminent scholars. But I am especially grateful to Jason Frank for organizing the original American Political Science Association session from which this forum emerged as well as to Qui Parle—of which I once served as an editor—for publishing the results.

In The Last Utopia, I offered an account of the recent ascent of international human rights, pushing back against emerging historiography that showcased continuity and necessity for the sake of providing a movement the authority of a deep past. But I never denied continuities absolutely, even as I decried the omission in the existing literature of lost roads into other futures, the presentation of drastic conceptual and practical transformation as if it had never occurred, and the elimination of the contingency of what were in fact entirely surprising developments.

Yet history is always the forum for a complex relationship between the ongoing and the adventitious. It seems obvious—it goes without saying—that without Jesus Christ there would have been no church, and with no church there would have been no Reformation, and so on and so forth. Self-evidently, in fact, some continuity back to the beginning of time is required for any later event to occur. Even more continuity holds between the French Revolution and human rights movements today, or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and our own international human rights politics.

Read now at Duke University Press

Articles

International Law, Human Rights, and Politics

Claude Lefort

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

International law: is it law? [Le droit international est-il du droit?] The question is not a new one: it was posed immediately after World War I, when the League of Nations took up the task of establishing the rules by which its members would abide—although at the time there was merely question of a Europe-wide law. What had formerly been known as the law of nations [droit des gens] served little further purpose than to remind sovereigns of the boundaries they must not overstep in the conduct of war. With regard to the obligations that stemmed from treaties contracted between states at the end of a conflict, their fulfillment depended upon the goodwill of the contracting parties, each of which was tempted to call the status quo into question if the relationships of force [rapports de force] were found to have shifted. For the first time, the League of Nations declared its assumption of responsibility for order in Europe by pursuing the implementation of a state of lasting peace [paix permanent]. This did not mean, as we have said, that all war was from then on rendered unlawful, for the League recognized the right of self–defense and the 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact (named for its principal protagonists) gave way to propositions concerning a new state of war.

International law: is it law? The question returns after the end of World War II with such heightened force that the United Nations sets standards to which all states must conform, even beyond European borders: they now claim to legislate at a global scale.

Read now at Duke University Press

Coercive Cosmopolitanism and Impossible Solidarities

Nikita Dhawan

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In recent years, an increasing number of global citizens’ movements have taken “justice” as their explicit goal. At issue here are the scope and scale of struggles for justice: What are the boundaries of justice, and how are they being renegotiated? In contrast to those who, committed to domestic justice, contribute to the well-being of their immediate communities and fellow citizens, theorists and activists in the field of transnational justice argue for a broader and deeper commitment that would encompass strangers both within and beyond state borders. They argue that in a globalized world our duties and responsibilities are not limited to our fellow citizens. A concurrent effort emphasizes the economic, political, cultural, and sexual aspects of injustice. The increasing scale and velocity of economic, cultural, and technological connectivity, along with the speed of global flows of capital, commodities, people, and ideas, have led some to claim that a profoundly new global condition has emerged, marking the end not just of borders but of empires too. Challenging imperialist globalization lies at the heart of counterhegemonic movements that bring together the concerns of groups as diverse as urban slum dwellers and sex workers, war crimes victims and metropolitan anarchists. Accordingly, these movements focus on human rights and on the equitable distribution of resources, as well as politics of recognition and representation, to ensure that all members of the world society have equal opportunities and parity of participation.

Read now at Duke University Press

“From Figure to Ground”: A Conversation with Eyal Weizman on the Politics of The Humanitarian Present

Eyal Weizman and Zachary Manfredi

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The following dialogue between Zachary Manfredi and Eyal Weizman took place in the spring of 2013. The primary topic of discussion was Weizman’s recent book The Least of All Possible Evils: Humanitarian Violence from Arendt to Gaza. The book traces the logic of “the lesser evil” as it plays out in three different sites: Rony Brauman’s role as the leader of Médecins sans frontières in the Ethiopian famine of 1983; a recent trial involving the wall between Israel and Palestine; and the use of forensic evidence in human rights tribunals. Covering a broad range of topics (military and humanitarian interventions, the relationship between left activism and biopolitics, the development and deployment of forensic technologies, the history of testimony in human rights tribunals, the production of visual fields of violence, and the politics of genocide), the interview’s themes all relate to the larger question of how new political practices and technologies of documenting violence have reconfigured the worlds of human rights and humanitarianism.

Read now at Duke University Press

Review Essays

Animating Space: Tracing the Construction of the Political in Ariella Azoulay’s Civil Imagination

Megan Alvarado Saggese

A review of Azoulay, Ariella, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London: Verso, 2012).

Read now at Duke University Press

A Just Grammar: Unspeakable Speech in Robert Meister

Christopher Patrick Miller

A review of Meister, Robert, After Evil: A Politics of Human Rights (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).

Read now at Duke University Press

For the Love of Democracy: On the Politics of Jacques Rancière’s History of Literature

Emily O’Rourke

A review of Rancière, Jacques, Mute Speech, translated by Swenson, James (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011).

Read now at Duke University Press

A Figure in Law and the Archive: Samera Esmeir and the Making of Juridical Humanity

Genevieve Renard Painter

A review of Esmeir, Samera, Juridical Humanity: A Colonial History (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2012).

Read now at Duke University Press

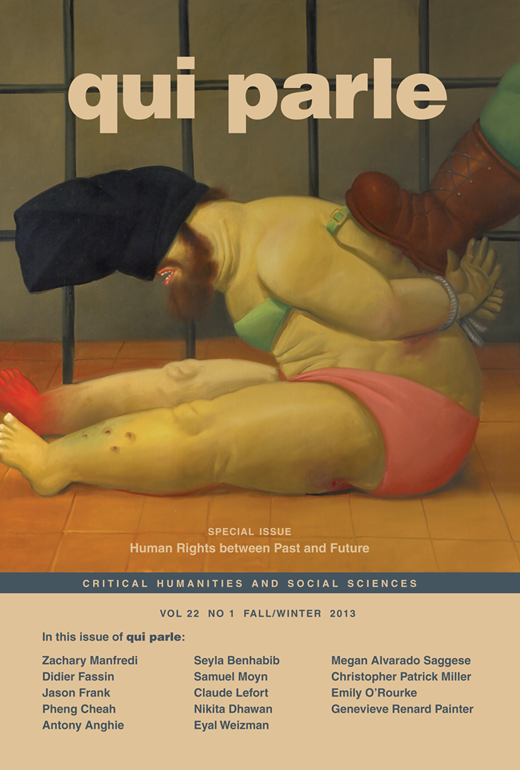

Cover: Fernando Botero, Abu Ghraib 60, 2005. More info.

Volume 22.1 is available at Duke University Press, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.