Articles

Crossing the Line: Blasphemy, Time, and Anonymity

Colin Jager

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

According to anthropologists and sociologists, the sacred depends upon boundaries. “Things set apart and forbidden” is how Émile Durkheim defined the sacred in The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1915), emphasizing that sacred things were set apart in such a way that they became the center of the social whole.1 For Durkheim, religion began when social groups performed rituals as a way of binding together a community; these actions produced a sense of the sacred, rather than the other way around. The true content of religion was to be found, then, in the manner in which it enabled humans to represent to themselves the social unit of which they were a part. In his desire to sort the sacred from the profane, Durkheim almost certainly overemphasized the coherence of the social whole.2 But the point remains that cultures, even loosely organized ones, depend upon separation, the demarcation of boundaries, and the leveling of injunctions against their violation.

Examples of such a dynamic abound. Early in Terrence Malick’s 2011 film The Tree of Life, for instance, a father tells his very young son Jack to stay out of the neighbor’s yard. He draws a faint line in the grass with a stick: “You see this line? Let’s not cross it. You understand?” We know, of course, that this is futile: no physical barrier exists here, just an imaginary line that no toddler will be able to comprehend, much less respect. Not surprisingly, the next scene shows Jack playing happily on the far side, and the father calling him back. There is a deep sense in which the father’s gesture is a futile one: to draw a line, or create a forbidden zone, is also to invite its violation. Indeed, transgression seems built into the idea of a boundary itself: we may know cognitively where the lines are drawn, but we don’t really experience their power until we cross them.

Read now at Duke University Press

Base, Vile, and Depraved: Blasphemy and Other Moral Genealogies

Molly Mcgarry

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

When British citizen Sebastian Horsley set off from London to promote his new book, Dandy in the Underworld: An Unauthorized Autobiography, and landed at Newark airport, he fully expected to gain entry into the United States. Horsley, a writer, artist, and overall self-produced gadfly, trafficked in quotable quips like “I can count all the lovers I’ve had on one hand . . . if I’m holding a calculator.” The Soho dandy was most notorious for having voluntarily undergone a crucifixion for art’s sake in the year 2000. Much like his trip to New Jersey, that provocative performance ended in spectacular failure as Horsley passed out and then fell off the cross when the footrest broke. Eight years later, Horsley was detained at Newark, questioned for eight hours, and eventually denied entry into the United States. In the aftermath, he reported: “I was dressed flamboyantly—top hat, long velvet coat, gloves. . . . My one concession to American sensibilities was to remove my nail polish. I thought that would get me through.” This confluence of ostentatious self-presentation with infamous debauchery and blasphemous performance art may have been factors in Horsley’s barment at the border, though none of these were excludable offenses in US immigration law. The official charge was “moral turpitude,” the evidence of which was supplied by his memoir itself.

The vague definition of moral turpitude (from the Latin turpis, meaning “ugly, foul or disgraceful”) as “base or shameful character” found a convenient fit with Horsley’s self-professed drug-and “prostitute-riddled past.” As an Anglo-American category, moral turpitude enfolds residual religious ideas about the body, character, and conduct with secular understandings of sex, race, and citizenship. At the borders of these categories, as well as at the borders of the United States, legal abstractions become material realities with pernicious effects. Conviction of a crime of moral turpitude can be used to impeach a witness, disbar a lawyer, bar an immigrant, or deport a lawful permanent resident from the country.

Read now at Duke University Press

Ready-Made Artist: The Genealogy of a Concept

Caire Fontaine

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

1. The ready-made is an aesthetic object that has no aesthetics, or whose principle of individuation is not aesthetic. “The choice of the Ready-made,” Duchamp states in 1961, “was never dictated by some aesthetic delectation. The choice was based on a reaction of visual indifference with at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste . . . in fact a complete anesthesia.” In the Dictionnaire abregé du surréalisme (1938) it is stated that the ready-made is a usual object promoted to the dignity of an artwork by the choice of the artist. The artist’s dispassionate choice and the time when it takes place are the only factors that provoke the transubstantiation from the banal object to the work of art. Whatever object chosen in whatever moment by whatever singularity becomes an artwork: it’s a matter of time and potentiality.

2. In the notes on The Bride from 1915 and 1916, published in the Green Box, we can read that a ready-made is something profoundly linked to a moment, a date, an occasion; it’s like a frozen [End Page 57] instant (Duchamp defines the 3 Standard Stoppages as “hasard en conserve,” “canned coincidence”). Ready-mades are then compared to a speech pronounced for a certain occasion, but for whatever occasion the speaker specifies, “à l’occasion de n’importe quoi mais à telle heure.” What counts is the time of the speech, the exact date of birth of an event. The event being whatever, only its position in time will make it unique. That’s why the fetishism of the precise moment is not in contradiction with duplication and repetition: “the ready-made is nowhere unique . . . the replica of a ready-made delivers the same message.”

Read now at Duke University Press

New Sites for Slowness: Speed and Nineteenth-Century Stereoscopy

Arden Reed

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Somebody once asked Los Angeles artist Ed Ruscha, “How can you tell good art from bad?” He answered, “With a bad work you immediately say ‘Wow!’ but afterwards you think, ‘Hum? Maybe not.’ With a good work, the opposite happens.” As Ruscha suggests, most visual art worthy of the name does not reveal itself in a flash. Yet the average American spends between six and ten seconds looking at a picture in a museum or a gallery. So how can we create conditions for richer and more meaningful aesthetic experiences?

To address this problem I have formulated a new aesthetic category that I call “slow art.” It is not a collection of objects, as you might suppose; rather, slow art names a dynamic relationship. It transpires in the space between observer and object. Rather than thinking conventionally, in terms of aesthetic works, we must think in terms of reciprocal experiences—encounters between the beheld and the beholders, who register their perceptions in historically specific instances. As a set of experiences, slow art will be different for everybody. And as in quantum physics, changing the way we look changes what we look at.

Read now at Duke University Press

The Public Spaces of Contemporary Literature

Lionel Ruffel

Translated by Matthew H. Evans

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Very few concepts are transparently transhistorical, or globally global in a transhistorical sense. None of those that I commonly use, in my professional setting, are. Literature, the author, the text, the work—all these concepts are dated and situated. Moreover, only very few concepts cut across planes of existence as diverse (although related) as politics, culture, urbanization, territorialization, or domesticity. Public space, however, is one of those concepts that, although unqualifiable as “universal” in the sense of an anthropological structure, could be described as transhistorical, as global, and as traversing almost all planes of existence. The last fifty years have continuously attested to its importance. I say “fifty,” because in 1962 Jürgen Habermas proposed an archaeology of modernity around the conceptualization of public space. “Fifty,” because for fifty years all revolutions, all political upheavals have expressed themselves via the occupation of public spaces, up to and including Tahrir Square, Zucotti Park, and the Puerta del Sol. Because we are continuously reminded that the global network represents a new agora, a term for which “public space” might read as the modern translation. Because our hyper-urbanized world has come into being alongside spaces other than those places of privatization: parks, gardens, and what anthropologist Marc Augé terms “non-places” such as airports or shopping malls. And lastly, but for our purposes certainly not leastly, because one part of contemporary artistic production (and I refer specifically to those arts that modernity has habituated us not to see as public performances—notably literature and the visual arts, painting and sculpture) massively invests in public spaces, as in the case of performances in the literary field or in that art sometimes called relational, sometimes contextual.

Read now at Duke University Press

Being Beyond Politics, with Jean-Luc Nancy

Martin Crowley

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The work of Jean-Luc Nancy is consistently drawn to the site of an almost-encounter, to a line at once decisive and ever mobile. Writing on film, nuclear disaster, or the naked human body, say, Nancy returns to what we might think of as the line between determinate figures and a dimension that these figures imply, but by which they are by definition exceeded. Always attentive to the singular idiom of the phenomenon in question, Nancy situates the objects of his interest in relation to the broad horizon he calls “sense,” namely, the fact of existence, and our exposure to this fact, irreducible to any determinate signification, the opening to and of the world that is re-marked—but not appropriated—by any act of figuration. The interface along which this exposure takes place is accordingly this line between determinate figures (forms, organizations) and what we might view as their ontological condition of possibility, which plays this transcendental role to the precise extent that it is itself unavailable for figuration as any kind of foundation or ground (and so is perhaps best thought of as “quasi-transcendental”). My aim in what follows will be to explore the operation of this line in some of Nancy’s recent engagements with the question of politics, specifically, his comments on the proper place and responsibilities of political activity.

Read now at Duke University Press

The Metapolitical Structure of the West

Roberto Esposito

Translated with the assistance of Matt Langione

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

What is the essence of politics? Or, more importantly, does one exist? The European philosophical tradition has never stopped asking this question—if only because it has never produced a convincing answer. When Carl Schmitt, in his famous essay on the “political,” poses the question explicitly for the first time, he specifies from the outset that by essence he means neither an exhaustive definition nor even a particular content. Essence, rather, is the paradigm enabling us to understand what politics is in its originary character. Not coincidentally, his other point of reference is the term origin. After having identified conflict as the constitutive element of politics, he explains that, “As with the term enemy, the word combat, too, is to be understood in its original existential sense.” The application of this condition, for Schmitt, is meant to frustrate any bellicist interpretation of his words. Even an anti- war stance can be essentially political, provided it is carried out with the same polemical intensity as the conflict it seeks to avoid: “War is neither the aim nor the purpose nor even the very content of politics. But as an ever- present possibility it is its leading presupposition” (117).

Read now at Duke University Press

Review Essays

Sympathetic Distance and Victorian Form

Jesse Cordes Selbin

A review of Greiner, Rae, Sympathetic Realism in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

Read now at Duke University Press

An Emotional Hegel

Alex Dubilet

A review of Pahl, Katrin, Tropes of Transport: Hegel and Emotion (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2012).

Read now at Duke University Press

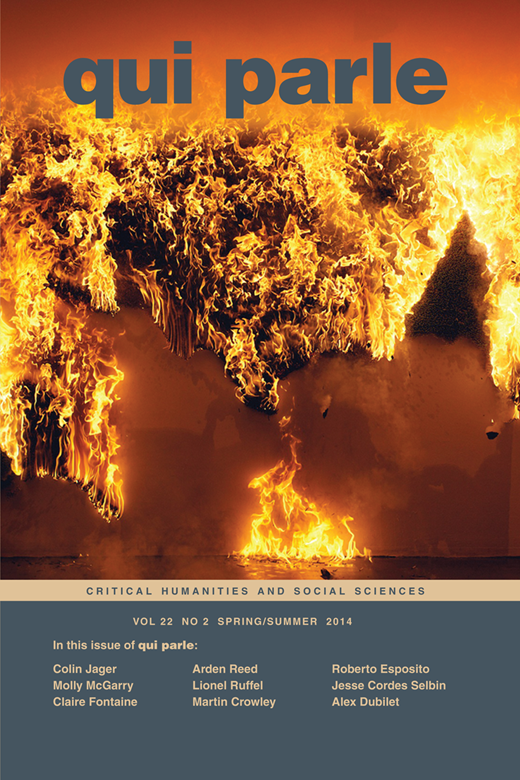

Cover: Claire Fontaine, Untitled (America Burning), 2013. More info.

Volume 22.2 is available at Duke University Press, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.