Articles

Reconciliation Romance: A Study in Juridical Theology

Christopher Bracken

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In 1984, Ronald Edward Sparrow, a member of the Musqueam Indian Band in Vancouver, was charged with fishing with a net longer than the length allowed by the band’s food fishing license. Sparrow did not dispute the facts. He responded that the license was inconsistent with Section 35(1) of the Constitution Act of 1982, which states: “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.” The Crown argued that the provincial Fisheries Act had extinguished the band’s Aboriginal right to fish. The assumption that an act of legislation has the power to extinguish an Aboriginal right dates back to a case called St. Catherine’s Milling. In May 1885 the province of Ontario petitioned the High Court to stop the company from logging on land northwest of Lake Superior. The province explained that it had not granted the company permission to log. The company responded that it had paid the Dominion of Canada for permission to remove two million feet of timber, arguing that the Dominion of Canada had acquired title from the Saulteaux First Nation in the Northwest Angle Treaty of 1873.

Read now at Duke University Press

In Medias Res: Visiting Nalini Malani’s Retrospective Exhibition, New Delhi, 2014

Mieke Bal

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

It was 2:50 p.m. on Sunday, December 21, 2014, the last day of the last chapter of a tripartite retrospective exhibition of Nalini Malani in the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in New Delhi. Eager to spend as much as possible of the mere three hours I had remaining to me with the works, which I knew to demand durational looking, I first did a quick reconnoitering walk-through. In the middle gallery—one of three—a uniformed guard stood next to an enormous charcoal wall drawing. He diligently supervised the public, ensuring that they would not come too close and smudge the drawing; charcoal smudges easily, and this would ruin the work. The drawing was a larger-than-life nude woman, her height combined with her low position compelling a kind of crotch-shot look that invariably makes one uneasily complicit in the culture of exploitative, or even abusive, “looking” familiar to pornography. The figure returns a fiery look, as if preempting our lack of modesty, confronting the visitor with her fury that, before she became a drawn figure, she directed at her treacherous husband, Jason. The title, Medea as Mutant, explained enough, or so I thought.

Read now at Duke University Press

Civility, Academic Freedom, and the Project of Decolonization: A Conversation with Steven Salaita

Evyn Lê Espiritu, with introduction by Jasbir K. Puar

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Professor Steven Salaita, the author of six books, most notably Israel’s Dead Souls, works in the fields of Middle East studies, comparative settler colonial studies, Native American studies, and Indigenous studies. He is also a prolific writer for alternative news outlets such as Electronic Intifada and Mondoweiss. As an outspoken critic of Israel and a pro-Palestinian activist, he has been integral to political efforts to tear open the possibilities of academic freedom for those aligned with the Palestinian struggle.

Recent events in Professor Salaita’s life brought three issues of longtime importance into conjuncture with each other: academic freedom, faculty governance, and the question of liberation in Palestine, especially when explicitly linked to Indigenous studies and the settler colonial status of the United States. Professor Salaita was fired—some like to liberalize it by saying “unhired,” but let’s be clear that per the widely accepted protocols of university labor practices he was indeed fired—from a tenured position at University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (uiuc) in August 2014, just weeks before he was about to start teaching, ostensibly for tweets deemed “uncivil.” These tweets were written during a fifty-one-day-long Israeli military assault on Gaza, a carnage that surely might make us pause at the use of the term “uncivil.”

Read now at Duke University Press

Revolution from Between: Latour’s Reordering of Things in We Have Never Been Modern

Laura Hengehold

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In The Order of Things, Michel Foucault notes that ethnology was only possible due to an “absolutely singular event which involves not only our historicity but also that of all men who can constitute the object of an ethnology.” This is a possibility

that properly belongs to the history of our culture, even more to its fundamental relation with the whole of history, and enables it to link itself to other cultures in a mode of pure theory. . . . Obviously, this does not mean that the colonizing situation is indispensible to ethnology. . . . But just as [psychoanalysis] can be deployed only in the calm violence of a particular relationship and the transference it produces, so ethnology can assume its proper dimensions only within the historical sovereignty—always restrained, but always present—of European thought and the relation that can bring it face to face with all other cultures as well as with itself.

Bruno Latour mentions Foucault once in We Have Never Been Modern, and only indirectly—to deny the supposed “death of man.” Nevertheless, I would argue that this book carries out a sustained dialogue with Foucault’s work in general and with The Order of Things in particular.

Read now at Duke University Press

Violence and Mechanism: Georges Canguilhem’s Overturning of the Cartesian Legacy

Stefanos Geroulanos

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In a television interview with Alain Badiou broadcast on January 23, 1965, Georges Canguilhem scandalously declared that philosophy could not be judged on the basis of the truth-value of its claims.

Badiou:

Do you think that there is no philosophical truth? You are going to scandalize us with this!

Canguilhem:

Oh I don’t think that I will scandalize you personally! But I would say, there is no philosophical truth. Philosophy is not a genre of speculation whose value could be measured by the true-or-false.

Badiou:

In that case, what is philosophy?

Canguilhem:

Although we cannot call philosophy true, this does not mean that it is a purely verbal or purely gratuitous game. The value of philosophy is a different matter than the value of truth, which value of truth must be expressly reserved for scientific knowledge.1

Perhaps Canguilhem’s most forcefully anti-Cartesian moment, this exchange reveals a great deal about a philosopher who had clocked nearly twenty years as inspector general of philosophy and as president of the French agrégation committee responsible for granting teacher status to philosophy students. In his pedagogy, as in his thought, Canguilhem maintained a conception of the relation of science and philosophy that was fundamentally non-if not anti-Cartesian: philosophy could no longer aspire to truth; it was not science; it did not coincide with science.

Read now at Duke University Press

Review Essays

The Fortress Deserted: Bersani’s Pastorals

Ramsey Mcglazer

A review of Bersani, Leo, Thoughts and Things (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

Read now at Duke University Press

Out of the Spirit of the Medieval: Andrew Cole’s The Birth of Theory

C. F. S. Creasy

A review of Cole, Andrew, The Birth of Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

Read now at Duke University Press

The Nation in Pain: Elaine Scarry’s Idiosyncratic Political Theory

R. D. Perry

A review of Scarry, Elaine, Thermonuclear Monarchy: Choosing between Democracy and Doom (New York: Norton, 2014).

Read now at Duke University Press

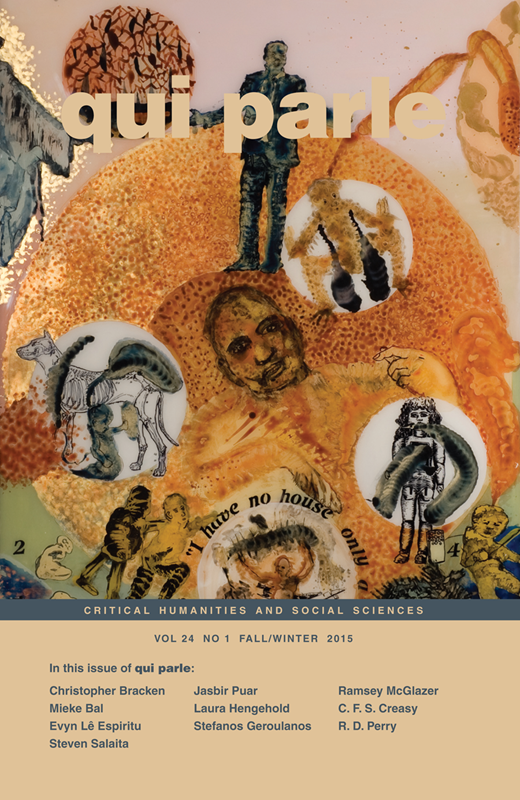

Cover: Nalini Malani, Twice Upon a Time, 2014. More info.

Volume 24.1 is available at Duke University Press, Project Muse, and JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.