Cultural Identity and the Promise of Literature

Hyphenated Identity: Nationalistic Discourse, History, and the Anxiety of Criticism in Salman Rushdie's Shame

Nasser Hussain

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

I may as well begin with an anecdote: on my last trip

home to Pakistan, my parents, with a curious mixture of

pride and shame, introduced me to their friends as a graduate

student in history. One such friend asked me the question I

had been dreading, "what history?" "British colonialism and

Indian history, I suppose," was my mumbled reply. The

friend, horrified that I was using my father's money to add

to the body of knowledge of the "aggressors" across the

border, retorted "and why not Pakistani history?" There

were any number of reasons I could have offered. After all,

I'm not even sure what Pakistani history is. Is it the narrative

of the forty-two years that have elapsed since the Muslims

demanded that the departing British rulers divide India into

two states, one for the Muslims and the other for the Hindus? Or, since the nationalism that produced Pakistan distinguished itself on religious terms, is it the history of the Indian Muslims traced back through the centuries? Either way,

I’m not very interested in the former and do not believe in

the latter.

Read now at JSTOR

The Cut That Binds: Philip Roth and Jewish Marginality

Eric Zakim

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

For years, the American Jewish intellectual has survived––and even flourished––on the belief that marginal existence brings with it extraordinary critical powers.

According to this belief, the typical Jewish intellectual stands

between worlds––Jewish and gentile––on the margin of

each, and from this position gains a vantage on both, a vantage unavailable to members of either community. Thirty-one

years ago in Partisan Review, the historian Isaac Deutscher

described this place––somehow marginal to both worlds––as

the fundamental aspect of Jewish intellectualism. Though

Deutscher's model emanates from European examples

published in America after the destruction of European

Jewry, the article speaks with an optimism that seems geared

for a singularly American audience:

“Have [Spinoza, Heine, Marx, Rosa Luxemburg,

Trotsky, and Freud] anything in common with each

other? . . . They had in themselves something of the

quintessence of Jewish life and of the Jewish intellect.

They were a priori exceptional in that as Jews they

dwelt on the boundaries of various civilizations, religions, and national cultures. They were born and

brought up on the borderlines of various epochs.

Their minds matured where the most diverse cultural

influences crossed and fertilized each other. They lived

on the margins or in the nooks and crannies of their

respective nations––they were each in society and yet

not in it, of it, and yet not of it...

Read now at JSTOR

Beheaded Sun (Soleil Cou Coupé)

Jean-Luc Nancy

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

They call you Chicanos. That name abbreviates your

name, Mejicanos, in the language that was yours, and has

not always remained the language of each one of you. They

have given you back your name, cut. In which language?

What is the language of this word, your name? It is at the

same time the idiom of a single name, and it is your way of

cutting, of mixing languages: babel without confusion, the

one you speak, and the one your poets write. They have cut

both the name and the language, and given them back to

you. (Who are "they"? The others, us, and you as well, you

these other selves in yourselves). It was a very old name,

older than that Castilian tongue into which it was first transcribed, copied, cut; it was an Indian name, and much older

than the name "Indian," that baptized Mexicans by force. A

mistake of the West imagining itself in the East, the name

"Indian" cut a terrain and a history from themselves, cut several territories and several histories, cultures of the sun, suns

of culture, of fire, of feathers, of obsidian and of gold. Iron cut into the gold.

Read now at JSTOR

Brides of Opportunity: Figurations of Women and Colonial Discourse in Lord Jim

Natalie Melas

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Colonial endeavor is strictly a male preserve. As

many critics have pointed out, women enter into colonial

discourse as figures for the exotic territory, or as virtuous

guarantors of racial ideology. In a close reading of Lord

Jim against the frame of Heart of Darkness, I propose to

explore the production of such figures and their function in

configurations of cultural identity. Explaining to his publisher why he interrupted his work on Lord Jim to compose

Heart of Darkness, Conrad wrote, “[Lord Jim] has not been

planned to stand alone. Heart of Darkness was meant in my

mind as a foil.” Heart of Darkness clearly offers the figure

of Kurtz, the paragon of Europe's civilizing intentions gone

mad in the colonial wilderness, as a foil for Jim, the undistinguished outcast of the imperial service who redeems himself in an obscure colonial outpost. A less obvious, but

equally provocative correspondence obtains between Kurtz's

women and Jim's girl. Reading the girl as an enigmatic conflation of Kurtz's Intended and his savage mistress, I will

propose that she ultimately calls into question any sense in

which Jim can be said to redeem the civilizing intentions of

the colonial project which Kurtz so gruesomely foiled.

Read now at JSTOR

The Poetics of Politics: Yeats and the Founding of the State

David Lloyd

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The reading and rereading of Yeats's later poetry and

prose with a view to comprehending the political implications of his post-nationalist writing might well bring to mind

a remark of Bertolt Brecht's on Shakespeare's Coriolanus.

To an actor troubled by Shakespeare's representation of the

plebeians, Brecht insists on simply noting this fact,

"Because it gives rise to discomfort." Certainly Yeats continues to cause discomfort, at least to any critic unwilling to

separate the aesthetic too readily from the political. The difficulty lies most evidently, of course, in the fact that we must

acknowledge, when all quibble and interpretation "is done

and said," the avowed authoritarianism if not downright

fascist sympathies of his stated politics, while at the same

time acknowledging the power of his writing to return and to

haunt. I do not think that these last terms, borrowed from a

Yeatsian lexicon, are too strong: it is as if the very obsessiveness of Yeats's own later poetry, living and reliving its

relatively sparse themes and symbols, speaks to a situation,

at once "psychic" and "political," which we have yet to work

through.

Read now at JSTOR

Joyce's Irish, Beckett's French: Expatriation and the Politics of Cultural Identity

Tadeusz Pióro

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

“One of the proofs that our countries are still undeveloped is the lack of naturalness in our writers: another

is the absence of humour, because humour only arises

from the natural.”

––Julio Cortázar,

Around the Day in Eighty Worlds

Cortázar's dismay at the undue gravity of his fellow

Latin Americans may help to illuminate the stylistic problems

involved in the establishment of cultural identity by two Irish

expatriates, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. Cortázar's

reference to a lack of development suggests the existence of

a universal narrative of ethical development determining the

relative positions of various national cultures: Argentine

writers lag behind their French and English colleagues, such

as Robert Graves or Simone de Beauvoir, to use Cortázar's

examples. "Naturalness" is a sign of advanced development,

implying that somehow English and French writers have

been able to return to their originary, "natural" state, thanks

to which they can publicly be humorous. Humor differs

from the comic in that it is the result of a conscious effort,

successful due to a sufficient degree of development which

allows for an effacement, or concealment, of this effort and

thus an appearance of urbane "naturalness," while the comic

does not necessarily require such express intention.

Read now at JSTOR

Language, Identity, and the French Revolution: A View from the Periphery

Peter Sahlins

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In 1627, Doctor Luis Baldo, honored burgess of

Perpignan, addressed a printed pamphlet to Philip IV. Describing the loyalty of the inhabitants of Roussillon and Cerdanya, and in particular the courage of the Cerdans in their

resistance to French incursions into Catalonia, Baldo underlined their loyalty and identity as Spaniards:

“The people are naturally more Spanish than those of

the other provinces of Spain; and they have such a

notorious antipathy and natural hatred of the French,

their neighbors, that it cannot be described in writing.

Their feelings are so extreme that a son, born in the

counties, abhors with a natural hatred his father, born

in France.”

In the spring of 1789, one hundred and thirty years after the

annexation of the County of Roussillon and part of the Cerdanya by the French monarchy, the three dozen rural communities of the French Cerdagne expressed a developed

animosity toward Spaniards while asserting their identity as

subjects of and devoted loyalty to the French king. They

complained of Spanish seigneurs who collected heavy dues,

of Spanish proprietors who, exempted from paying personal

taxes, bought up their lands, and even of Spanish cattle

which took resources away from the "subjects of the French

king."

Read now at JSTOR

Justifying the Page

Ann Gelder

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Mark Twain met the inventor James W. Paige in the

Colt Arms Factory in 1880, and was enticed, mesmerized,

and finally deeply disappointed by Paige's creation: a mechanical typesetter which had promised, at least to Twain, to

revolutionize printing. James Cox describes the fascination

that the machine held for Twain:

“He spoke of it as a cunning devil at one time; at another, he contended that it was next to man in intricacy and at the same time it surpassed him in perfection; at still another, he wrote that he loved to sit by

the machine by the hour and merely contemplate it.

Never was Twain more enamored of an object, unless

it was Olivia Langdon; if she was the goddess he

revered, it was the demon that possessed him and on

whom he wasted his fortune and almost sacrificed his

sanity. In his obsessed vision, the machine was both

an intricate world and a mechanical brain whose infinitely interrelated parts he could half comprehend.

. . . More than that, the machine was uniquely

wedded to the printed word; it was, after all, a kind of

automatic writer capable of working tirelessly with

speed and precision.”

Read now at JSTOR

Stowe’s Authentic Ghost

Eva Cherniavsky

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In a recent interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, Mary Beth Whitehead, the repentant surrogate mother in

the Baby M case, cast her refusal to abide by the contract she

had signed in the light of a higher principle of social coherence: "Mother and child––that is what America is built on."

No more nor less could be said in her defense, the tone of

this assertion implies. And the exasperated interviewer

comments: "[Whitehead] twists most questions back to her

basic tune: A mother is a mother is a mother." But Whitehead's claim is at once more complex and more compelling

than the interviewer's flippant dismissal suggests. For, as

Whitehead herself clearly intuits, a mother, unlike a rose, is

not merely a function of her inscription, an object that language easily circumscribes, however little it can make it signify. On the contrary, motherhood operates here in excess

of the mother's contractual obligations, of what the law

might construe as her claim to her child. And it is precisely

by virtue of this excess that motherhood is made to signify.

Read now at JSTOR

Franklin’s American Odyssey

Mitchell Breitwieser

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Increase Mather's writings on physical phenomena,

as Robert Middlekauff contends, stress the violent, the disastrous, the unpredictable: they emphasize that nature is one

of the languages in which an unknown god speaks his cryptic, only fitfully explicable messages. His son Cotton

Mather's writings on nature, however, investigate discernibly regular phenomena, or seek to discover the regular

operations of what had seemed to be unpredictable or only

partially knowable. Cotton Mather knew very well that he

was implicitly assuming a very different kind of divine discourse than his father had, a kind of speaking god he desired

to be the case, one who could be understood, spoken with, and satisfied. As with his desire in general, Cotton Mather

knew the intrinsic tendency of this desire, and he was careful

to curtail or decrease it before it reached its goal: at those

moments when his explications of the regular reached their

full momentum, he interrupted them with accounts of the absolutely inexplicable and terrifying. He staged a curtailment

of his desire by the pure force of Increase's god: rather than

the clear and circular communication he longed for, there

would be infinite, mandatory and ultimately inadequate

propitiation, appeasement, sacrifice or expenditure on his

side, and a ravenous recipient on the other.

Read now at JSTOR

Book Reviews

On Jon R. Snyder, Writing the Scene of Speaking: Theories of Dialogue in the Late Italian Renaissance

Heather James

A review of Snyder, Jon R. Writing the Scene of Speaking:

Theories of Dialogue in the Late Italian Renaissance. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1989).

Read now at JSTOR

On Kathryn Gravdal, “Vilain and Courtois”: Transgressive Parody in French Literature of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

Carolyn Duffey

A review of Gravdal, Kathryn. “Vilain and Courtois”:

Transgressive Parody in French Literature of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989).

Read now at JSTOR

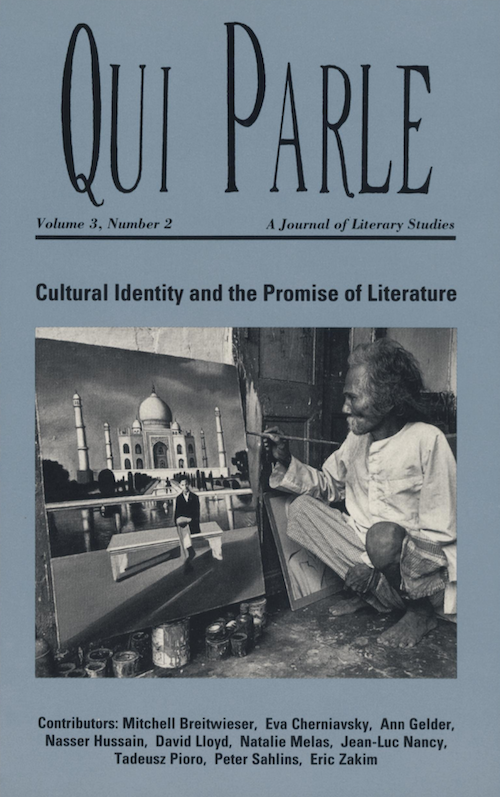

Cover: Babuton Methei of Sylhet, Bangladesh, paints portraits of his clients in front of a background of their choice, in this case the Taj Mahal. Photograph © Tom Learmouth.

Volume 3.2 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.