Different Subjects

Baudelaire’s Modern Woman

Peggy Kamuf

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

What of Baudelaire's women? What of "feminine presence" in Les

Fleurs du mal?

Without a doubt Baudelairean lyricism is stamped everywhere, or

almost, by a feminine appeal or an appeal to femininity. And yet that

appeal, precisely because it cannot easily be separated out from the

poet's "own" voice, could easily mislead us into some credulous

cherchez-la-femme scenario. Elsewhere I have wondered how the limits

of this "feminine presence" can be determined, given, among other

things, the constant possibility of ironic doubling, of the "vorace

Ironie" named in "L'Héautontimouroménos": "Elle est dans ma voix,

la criarde! / C'est tout mon sang, ce poison noir! / Je suis le sinistre

miroir/ Où la mégère se regarde." Because the poet's voice is not

strictly his own, but has been invaded or infected by this piercing

"Elle," because the poet can be a mirror for another's self-absorbed

gaze, one cannot place too much faith in thematized figures as

representatives of some "feminine" or "masculine" presence. The one

can always stand for or hide the other, and not according to some stable

rule of substitution, but in a voracious, all-consuming movement that

leaves no certainty standing in its wake.

Read now at JSTOR

Going Straight with Gilda

Greg Forter

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

For the briefest of instants, scarcely apprehensible, before Gilda

erupts onto the diegetic scene of Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946), the camera broaches her physical presence as a mere somatic possibility.

Attaching itself yearningly to Ballin's searching glance, seeking out for

luxurious illumination the object of his question––"Gilda, are you decent?"––it manages only to frame instead, for less time (it's true) than it

takes to bat an eyelid, a vacant room, redolently feminine, surprisingly

light, into which the till-now-invisible bride then suddenly tosses her all

but glowing head. There––but where?––where this woman's body

ought to be, there in the light-world that ought by all rights to display it

to rich advantage, all eyes are trained for one anxious moment on the

sumptuous nothingness of an empty frame, the lavishly curtained

backdrop of a bare-because Gilda-less-bedchamber. The film thus

suspends on the brink of predication the hermeneutic sequence that's

initiated, at least explicitly, by its first mention of women (Ballin to

Johnny: "This I must be sure of: that there is no woman anywhere"),

but that's been evoked anyway, however discreetly, by the very extent

of a diegetic dilation that withholds from sight for a full fifteen minutes

the movie's eponymous heroine.

Read now at JSTOR

Gide Writing Home from Africa, or From Biskra with Love

Michael Lucey

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In 1924 Andre Gide published the final version of his memoirs, Si le grain ne meurt (If It Die), which he had been working and reworking

for a number of years. It is hard not to read these memoirs as a form of

self-analysis, a place in which Gide tries to construct in narrative form

an explanation of his own sexual development, or perhaps we should

say a place where he confronts the difficulties that kind of explanatory

effort inevitably causes. It is in the context of such difficulties that one

feels drawn to read the following scene, described by Gide on only the

second or third page of his book. The Gides are on a visit to his father's

side of the family in Uzès, and on this particular day they are visiting

"les cousins de Flaux":

“My cousin was a very beautiful person and she knew

it .... I remember very well the dazzling whiteness

of her skin-and I remember it especially well

because the day I was taken to see her she was wearing a low-necked dress.”

Read now at JSTOR

The Analogy of Form: Mourning and Kant’s Third Critique

Lisa Freinkel

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

So we were told, my brother, sister, her husband, my mother and I,

in September, during the macabre two weeks it took to get my father's

body home. He died in Leningrad, and between the 2 a.m. phone calls

to Russia and the daily conferences with Seymour, our friendly if not so

benign funeral director, not to mention the calls to our pals at the airlines––conversations which took on a luminous quality all their own

(the good news is he's back in the States; the bad news is he's stuck in

a hangar at JFK)––the episode gradually assumed the bleakly, blackly

comic contours of what Harold Bloom calls Faulkner's agon. For two

incredulous weeks, we were the Bundren's en route to Jefferson, each of

us whirring away in formless reflections; our minds blind, depthless.

We were occupying the same space, our "home," the house I grew up

in, spending bleary hours with yellow legal pads and the telephone in

what we were calling "the nerve center," perhaps to avoid calling it my

father's study, coming together, fitting together with fits of laughter

only.

Read now at JSTOR

Reading Lucy Snowe’s Cryptology: Charlotte Brontë’s Villette and Suspended Mourning

Anne A. Cheng

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

If it were only in dreaming that she could have, then it was dreaming that made her greedy. There must have been, too, a need for a secret, a shelter in which to wait for words that she could live by. For a

long time, the unsaid swells and stains its bearer with its shadow. It is

what we see surging forth––in the space between narrative and text,

between confession and the hidden subject––making the shape we

know this novel by, the narrative inside, the critique of the given.

What then is this gap between narrative and text? What haunting?

Why do almost all readers of Villette respond to Lucy Snowe with either ressentiment or a disturbing insistence? Why do we find her voice

so dispossessing when she is offering us her autobiography, a seemingly confessional narrative?

Read now at JSTOR

Swift and the Subject of Satire

Elizabeth Maddock

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

While the subject of this paper is Swift, the text I present will also

have been a reading of Lacan's essay, "The Agency of the Letter in the

Unconscious, or Reason Since Freud." I tell you this in order not to

mislead you––in order to make my direction clear to you. Yet this

rhetoric of revelation on my part may already be misleading, for I want

to argue that the subject exposes itself precisely through the act of hiding. Swift's satire, insofar as it announces itself as a game of hide and

seek, will ultimately direct us to the domain of this hidden and exposed

subject––to Swift as a subject and to the agency of the letter in the ruses

of literary subjectivity.

Read now at JSTOR

A Union Forever Deferred: Sexual Politics after Lacan

Barbara Claire Freeman

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

What is the value, assuming there is any, of Lacan's theory of feminine jouissance for contemporary feminist sexual and textual politics?

What are the politics of a Lacanian reading of femininity, and what way

of re-reading Lacan does a certain political position, call it a post-humanist feminism, demand or perhaps make imperative? If, with Terry

Eagleton, we define the political as "the way we organize our social life

together and the power relations which this involves," do the kinds of

power relations implied by a text such as Encore enable or disable contemporary feminist theories? Inevitably, Lacan's discourse does both.

And although there is always the possibility that I might "use it in

order to signify something quite other than what it says," my purpose

is to attempt to spell out how, and why.

Read now at JSTOR

Book Reviews

The Birth of an Author?

Adam Bresnick

A review of Rosenberg, David. The Book of J. With commentary by Harold Bloom. (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990).

Read now at JSTOR

On Frances Bartkowski‘s Feminist Utopias

Maud Gwynn Burnett

A review of Bartkowski, Frances. Feminist Utopias. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989).

Read now at JSTOR

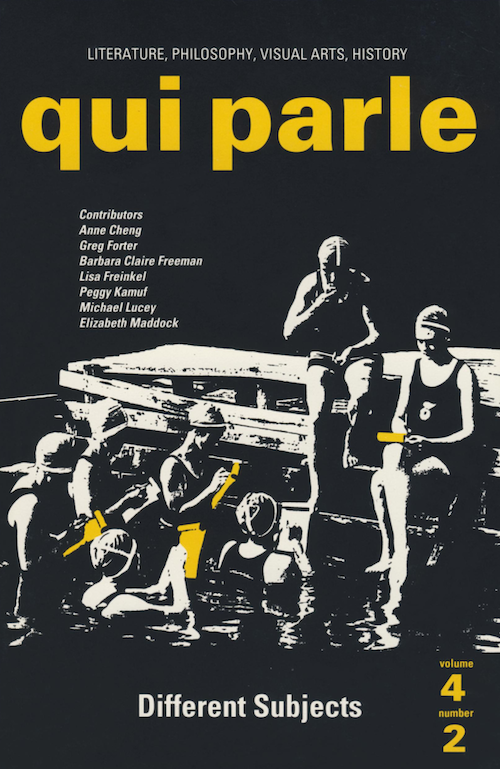

Cover: Photograph reprinted with permission from Underwood Photo Archive, San Francisco, California.

Volume 4.2 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.