Articles

Sadism and Film: Freud and Resnais

Leo Bersani & Ulysse Dutoit

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Is there a non-sadistic type of movement? Would we go toward

the world if we were not motivated by destructive impulses? This

question––which we will first treat theoretically and which we will

consider in the context of two films of Alain Resnais––is at once

raised and elided in Freud's 1915 essay "Instincts and Their Vicissitudes." Toward the end of that essay, in his discussion of the instinctual vicissitude consisting in a change of content (a vicissitude

"discerned in a single instance only––the transformation of love into

hate") Freud claims: "At the very beginning, it seems, the external

world, objects, and what is hated are identical." The infantile ego

must defend itself against the external stimuli by which it is bombarded; "hatred" is at first a self-preservative reflex. But this repudiation of the world––of all the difference that threatens the ego's stability (indeed, at the beginning, its very constitution as a distinct identity)––is by no means limited to infancy. The ego's protective measures against a painful influx of stimuli from the external world

will, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), be hypostatized in the

"instinctual" need of all living organisms to return to the state of

inanimate matter. "As an expression of the unpleasure evoked by objects," Freud writes in "Instincts and Their Vicissitudes," hate

"always remains in an intimate relation with the self-preservative instincts" (14:139; emphasis ours).

Read now at JSTOR

Delicacy and Disgust, Mourning and Melancholia, Privilege and Perversity: Pride and Prejudice

Joseph Litvak

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In a well-known passage from one of her letters to her sister Cassandra, Jane Austen records her own response to Pride and Prejudice

(1813):

“I had some fits of disgust. . . . The work is rather too

light, and bright, and sparkling; it wants shade; it

wants to be stretched out here and there with a long

chapter of sense, if it could be had; if not, of solemn

specious nonsense, about something unconnected

with the story; an essay on writing, a critique on

Walter Scott, or the history of Buonaparté [sic], or

anything that would form a contrast, and bring the

reader with increased delight to the playfulness and

epigrammatism of the general style.”

That Austen can be driven to disgust not just by her own writing, but

by its very refinement, by what is most "light, and bright, and

sparkling" in it, comes as no surprise: the hyperfastidiousness she

evinces here confonms perfectly with the venerable stereotype of gentle Jane, where the gentleness or gentility in question easily assumes a

pathological or ideologically suspect character.

Read now at JSTOR

Preside at their Pleasures: Rousseau, Diderot, Kafka and the Ambivalence of Representation

Lincoln Shlensky

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In the preface to The Letter to M. d'Alembert on the Theatre,

Jean-Jacques Rousseau gives his readers an eloquent lesson in the

proper proportions of democratic discourse. Rousseau had written the

Letter as a response to d'Alembert's proposal, which appeared in the

article "Geneva" in a 1757 volume of the Encyclopédie, that a theatre

should be established in the city of Geneva. Before launching into a response to the article, Rousseau's preface gives reasons why his response

to d'Alembert's proposal should not be withheld. It is characteristic

of the Letter that these reasons seem at first glance to be mere stylistic

flourish; but, in keeping with Rousseau's narrating ethos, such acts of

stylistic bravado always double as rhetorical devices. The opening

paragraph announces Rousseau's decision to publicly break with

d'Alembert and, by association, with the whole project of the Encyclopédie, to which Rousseau had formerly contributed.

Read now at JSTOR

Spectre Shapes: “The Body of Descartes?” with an intervention by Peggy Kamuf

Andrzej Warminski

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

This title––"The Body of Descartes?"––quite rightly dresses the body

of Descartes with a question mark. The question mark is most fitting, for,

indeed, what we might want to identify under its garments as the body of

Descartes could turn out to be a ghost or an automaton––like those hats and

cloaks at the end of the Second Meditation that we judge (by the "pure

inspection of the mind") to clothe men but which may turn out to cover only

"spectres or feigned men" (des spectres ou des hommes feints). But these

shapes become all the more questionable if we remember that in context

they are the figures for a still more famous body of Descartes: the body of

the "piece of wax." In the same way that ordinary language almost

deceives us into saying that we see the same wax after it has undergone all

kinds of changes to its corporeal nature––when, in reality, what we do is

to judge by the pure inspection of the mind that it is the self-same wax

so it would deceive us into saying that we see men when we look out the

window at hats and cloaks passing in the street––when, in reality, what we

do is to judge by the pure inspection of the mind that these hats and cloaks

cover the bodies of men and not ghosts or automatons.

Read now at JSTOR

The Unease in Art History

James Elkins

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

I. Art history on the sickbed

Part of the constitution of the discipline of art history in the past

three decades is an uncertainty or unease about itself. This feeling typically appears as a medical metaphor: a disease or a "crisis in the discipline" with "symptoms" such as parochialism, moribund methods, or

lack of intellectual force. Theorists rush at it like doctors, clamoring

to be the first to pronounce a working cure. Some are prescriptive, setting out conservative canons (one such is W. M. Johnson, Art History,

Its Use and Abuse) or agendas of expansion and reform (such as Donald

Preziosi' s Rethinking Art History). Others are more descriptive, and

imagine their purpose to be the representation of the current state of

affairs (for example, David Carrier's Principles of Art History Writing, and Mark Roskill's What is Art History?). To a third group, the

patient has already died, and the task is to think ahead, to plan art history's successor (here one might name Hans Belting's The End of Art

History? despite its author's protestations that he is not writing about

the end of art history).

Read now at JSTOR

Book Review

On Valerie Traub‘s Desire and Anxiety: Circulations of Sexuality in Shakespearean Drama

Eve Sanders

A review of Traub, Valerie. Desire and Anxiety:

Circulations of Sexuality in Shakespearean Drama. (New York: Routledge, 1992).

Read now at JSTOR

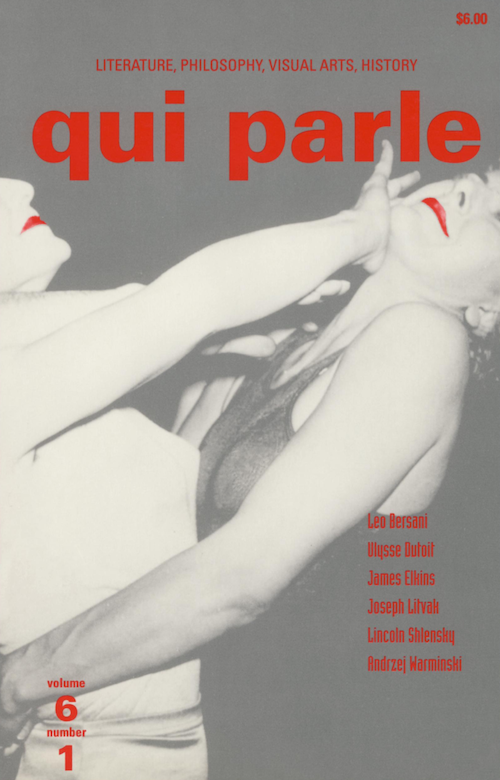

Cover: Photograph reprinted with permission from Underwood Photo Archive, San Francisco, California.

Volume 6.1 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.