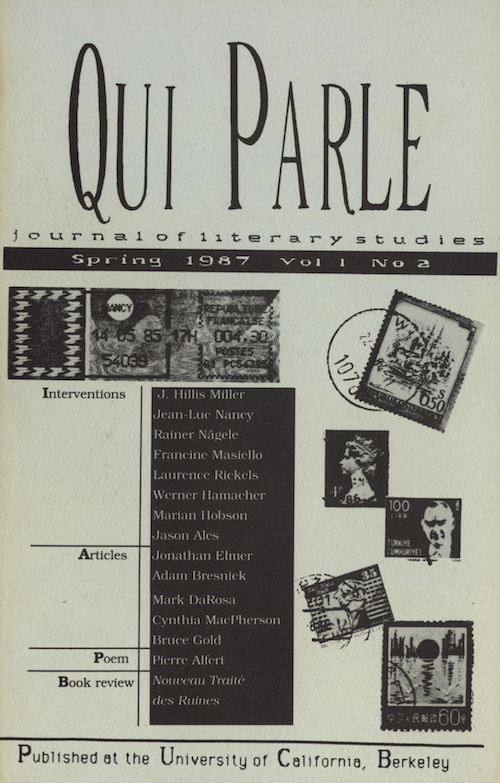

“Under Construction”

Prefatory Note

Peter Connor

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The interventions which comprise the first section of this

issue were received in response to a question formulated by the editors of Qui

Parle and addressed to a number of prominent literary critics and theorists of

literature throughout the United States and Europe. The question, reprinted on

the page immediately preceding the interventions, concerns the place of the

teacher and teaching in the institution, and the role of the student in the

pedagogical scene. Insofar as the problematic of formation or Bildung remains

constitutively incomplete, we shall have to keep this volume "Under

Construction." It is hoped that the publication of these responses will

encourage further debate around the many issues raised and discussed by our

present contributors, and the editors of Qui Parle urge readers to participate

via the columns of the journal.

The urgency of our question arises at a time

when the university is re-organizing its significance and when the effects of

the institution are being seriously questioned, perhaps most especially from

within the disciplines of the humanities.

Read now at JSTOR

Interventions

The Imperative to Teach

J. Hillis Miller

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The questions ask: Who or what (today) calls

on us to teach? Does that demand lay out a clear

road for us to follow? Is that road, if there

is one, "under construction," that is, I take it,

is it in the midst of a social or historical process into which we as teachers or students might

intervene, taking a hand in the work of construction? Is that road, if there is one, a one-way

street, Einbahnstrasse, presumably in that case

going straight from the teachers to the students,

with "Do Not Enter" marked at the other end, to

keep the students from driving the wrong way, in

defiance of the authority of the teacher?

The questions can be extrapolated a little,

perhaps down the one way street that waits to

be traversed, showing me the way to go: Is teaching a contingent addition to "literary study,"

or to "humanistic study" generally? Or, to put

it more simply, does reading, the reading of a

poem, a novel, or a philosophical text, for example, require teaching it or lead inevitably to

teaching it?

Read now at JSTOR

Untitled*

Jean-Luc Nancy

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Y a-t-il quelque chose qui appelle à l'en

seignement aujourd'hui plus qu’à une autre époque?

Je ne le pense pas, ou bien je ne le discerne pas.

Y a-t-il aujourd'hui un motif ou un mobile parti

culier qui mène à enseigner? je n’en vois pas.

En outre, de telles questions exigeraient, me sem

ble-t-il, qu'on spécifie de quel enseignement on

parle: c’est-à-dire, à quel niveau, dans quelle

discipline, dans quel pays, dans quelle institution,

sur le fond de quelle tradition. Mais votre dessein

n'est manifestement pas celui d'une pareille en

quête. Je répondrai done de manière très "person

nels" et en somme très empirique.

Read now at JSTOR

Two Lessons: The Tui-Report and K. in the Cathedral

Rainer Nägele

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Tui: a Brechtian Chinese word for a certain

kind of intellectual, derived from Tellect-Uel-In.

These literally confused intellectuals have the

task of protecting the socio-economic power structure of their society against any possible threat

from critical thought. In Brecht's China, for

example, the economy, i.e., the profits of the

emperor, is threatened by an over-abundant cotton

harvest. In order to drive up the dangerously

falling cotton prices, the emperor has the majority of the cotton secretly burned. The scarcity of cotton brings its price to astronomical

heights. The population is puzzled by this phenomenon; after all, everybody knows about the

rich harvest. Suspicion and rumors arise.

Quick and clever action is necessary to avoid

civil unrest.

Read now at JSTOR

Untitled

Marian Hobson

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

I translate this question, no doubt twisting

it, as: What appeals to teaching/learning today?

One answer is that the appeal is a case of "controlled appellation." Teaching/learning in institutions ends in the conferring of titles--the right

to prefix or suffix letters, or appellations, to

one's name. This conferring is not universal,

but controlled--the rights of appellation are graded,

part of a hierarchized academic transport system

(not for nothing do you speak of "tenure track"),

though not by any means secure "titres de transport." This grading, these grades, this graduation,

all this is central to the educational institution:

degrees are attributed, exams are "moderated" in

a term which tellingly joins the notions of presiding and of insertion of differentials, 'modus,'

means. This is power through distinction: the

distinguishing mark of a university as institution

is its power to confer marks of distinction; and

universities themselves are graded, they or academic

boards cross-validate each others' marks by a system

of external examiners, of University Grants Committee

assessors, etc.

Read now at JSTOR

The Road Belong Cargo

Laurence Rickels

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In Dialectic of Enlightenment Adorno and

Horkheimer argue that the university, like the rest of the culture industry and like the radio

in particular, is democratic: it turns all participants into auditors subjected to broadcast programs which are all exactly the same. This norm

of killing time represents the institutionalization

of Freud's discovery of the mechanism of repression;

it corresponds to the unceasing expenditure of unconscious psychic energy which accompanies the

effort to keep that which must not enter consciousness in the unconscious--in the all-pervasive public

sphere. The analogies that thus keep the public

sphere on this side of the Freudian system converge

in Totem and Taboo as the close encounter between

projection and cinematic projection. At the end

of these analogies, Freud's theory of phantoms

and the technical media finds confirmation and

realization in the Melanesian Cargo Cult, which

also makes a ghost appearance in 1913.

Read now at JSTOR

Untitled

Werner Hamacher

Translated by Adam Bresnick

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Dear Peter Connor:

One should reply to your question, of course,

with something more than a "relatively brief submission," namely with at least an exposition of

and tentative reply to those questions which arise

from questions and from forms of questions which,

following a long tradition of pedagogical questions

and questions about pedagogy, you use again today--or aujourd-hui. Qu’est-ce qui----donne----l'appel---- à l'enseignement----aujourd'hui----? These

questions about your question--I will suggest them

only very quickly--would be of the following sort:

Why what? Why gives and not takes? Why is the

call thought of as something which, rather than

taken, taken down, or taken in--be it from a specific situation, be it from a specific agent, subject, principle, preferably a moral one--will be

given? And if each call which issues is destined

to make demands on the one who is called (but this

is also questionable), is it already settled that

I will hear, that I will hear this call and hear

it as one destined for me?

Read now at JSTOR

Untitled

Francine Masiello

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Far from offering a rhapsodic celebration

of the attractiveness of university teaching (and

you must admit that your question invites this

kind of response), I feel obliged, instead, to

take stock of the neo-conservative climate of the

eighties and its effect on the academy. In particular, I am alarmed by the Reagan administration's narrow vision of the university and its

patent contempt for the heterogeneity of contemporary scholarly pursuits. Ranging from the

so-called advisory committee for accuracy in

academia to the proposed educational reforms

drawn by William Bennett, the initiatives of this

administration have been designed to monitor and

contain the range of dialogue articulated in the

classroom. Among his many pronouncements on university teaching, Bennett, for example, has demanded a reduction in the multiple offerings of

the liberal arts curriculum, calling an end to

what he deems the unnecessary frills of the humanities program.

Read now at JSTOR

Copie Blanche*

Jason Ales

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Une conversation inouïe: un parlait à plusieurs, trop pour vraiment se connaître, chacun

aussi attentif que s'il eût été seul à écouter,

peu jaloux, peu gêné par la concurrence faite à

ses oreilles, sages tous et silencieux sans s'être

entendus à l'avance, interdits, ne se permettant

que questions et acquiescements, ne prenant jamais

l'initiative de changer de sujet. Mais l'orateur

lui-même, l'avait-il choisi? Se contentait-il

de questionner quelque orateur supérieur et invisible? II semblait là sur ordre, comme sachant

qu’on faisait aussi son appel, aujourd'hui comme

hier, mais pour en référer à qui? N’y avait-il

donc, à chaque échelon de cette procession de

paroles, qu'acte de présence pour répondre à

l'appel?

Read now at JSTOR

Articles

Something for Nothing: Barthes in the Text of Ideology

Jonathan Elmer

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

If, instead of the question "What does this

text say?", we ask "What does this text want me

to say?", we perform the first gesture (doubtless

paranoid) in what would seem to be a reversal of

the normal power relations between a text and its

reader. No longer interested in invading the text

with an imperialistic determination to search out

"radical elements" in order to harass them into

confessing the "truth," we begin to set up a paranoid counter-intelligence system designed to protect ourselves from the infiltration of the text’s meanings which, posing as one of our own agents,

might trick us into disclosing the state secrets

of our bigoted, ideologically determined, sexually

neurotic, petty selves. Like any paranoid structure, however, this one is fantasmatic, since texts

cannot infiltrate us: at most, they can lure us

into their discursive system and, by making it seem

attractive to describe the contours of that system

(as though it were exterior to ourselves), they

generously allow us to announce triumphantly our

ideological complicity with them.

Read now at JSTOR

Tristan et Isault as a “Salle Aux Images”

Adam Bresnick

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

In a terse and provocative apothegm, Jacques

Lacan declared that "on n'est jamais amoureux que d’un nom." The Lacanian model of desire adumbrated in this little catch phrase seems to me particularly useful for a consideration of the medieval

legend of Tristan et Iseut, for throughout Tristan

et Iseut one is confronted with episodes in which

the fundamental mediation of representation--be it

nominal, narrational or pictorial--is presented to

the reader as that which deflects desire away from

its ostensible object back onto the represented image

or story itself. In contradistinction to the "realistic" point of view, which takes as its model what

might be called a naive mimetism (the text as a

secondary imitation of "the real world"), I will

argue that Tristan et Iseut is as much a narrative

about our love of narrative itself as it is a story

of love between two individual people. As we shall

see in the episode of the Salle aux Images, representation is presented as that which magnetizes our

cathexes in a manner simultaneously troubling and

enrapturing, for in the end Tristan et Iseut suggests that it is the image and not the reality

which has the upper hand in our affections.

Read now at JSTOR

The Socratic Disruption of Origins in The Birth of Tragedy

Marc DaRosa

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

The opening section of this paper will present, in a selective and strategic, but not altogether critical manner, various passages from The

Birth of Tragedy which characterize Nietzsche’s

treatment of "Socratic culture." Of course, it

is possible that any instance of selection represents an interpretive act, and therefore becomes

a "critical" gesture. However, by the end of the

essay, these isolated passages will have received

a more detailed exposition. They will reappear

wearing a second face, one which is more suited to

the complex and ambiguous nature of Nietzsche's

relationship to the "Socratic man." This double

(and duplicitous) reading is perhaps the only possible approach to a work which speaks in a plurality of voices, in which every statement is an

illusion that masks an illusion.

Read now at JSTOR

The Double-Edged Pen: Reading “A Peine” in Mémoires

Cynthia McPherson

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

Enfolded between the preface and the first

lecture of Mémoires: For Paul de Man is a concealed scene of pain, a scene easily overlooked

and forgotten. In "A peine," the proper name of

this hors d'oeuvre, which stands like an epitaph,

perhaps marking the temporary resting place of

Paul de Man, Derrida reads and remembers the pain

hidden in the phrase à peine. The ear of a

franco phone hardly hears the pain and hardship

in à peine, hardly remembers in the spoken word

the pain visible in writing. What follows is a

meditation upon the difficulty hidden in the

phrase "à peine" in relation to following in

life and in thought.

Read now at JSTOR

How Progress Eludes Us: Variations on a Theme

Bruce Gold

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content:

There was once a boy whose mother died

on the sidewalk in the night, but before she

collapsed she lurched forward, walking as if

one leg were shorter than the other. As her son

dashed forward and fell at her side, crying "Mamma! Mamma!" a tide of darkness seemed to

be sweeping her from him:

"Wait here! Wait here! he cried and

jumped up and began to run for help

toward a cluster of lights he saw in the

distance ahead of him, but the lights

drifted farther away the faster he ran,

and his feet moved numbly as if they

carried him nowhere. The tide of darkness seemed to sweep him back to her,

postponing from moment to moment his

entry into the world of guilt and

sorrow. (FLANNERY O'CONNOR)

Nonetheless, he had many more years to live...

Read now at JSTOR

Poem

Elégie californienne (extrait)*

Pierre Alféri

Nous sommes partis de Berkeley -

traversée

par la route à deux voies

taillant d'une main sûre dans le ruban des terres

deux bandes qui s'effrangent

au passage et au loin

se rafistolent,

la ville ou la forêt à l’égyptienne

défilait en parallèles insoucieux l'un de l'autre...

Read now at JSTOR

Book Review

Nouveau traité des ruines by Giancarlo J. Lacina*

A review of Lacina, Giancarlo J. Nouveau traité des ruines (Trojan University Press, 1986)

Read now at JSTOR

Cover Design by Michael Macrone

*Published in French

Volume 1.2 is available at JSTOR. Qui Parle is edited by an independent group of graduate students at the University of California, Berkeley and published by Duke University Press.